XML and JSON: the tale of the tape

School of Data is re-publishing Noah Veltman‘s Learning Lunches, a series of tutorials that demystify technical subjects relevant to the data journalism newsroom.

This Learning Lunch is about XML and JSON, two popular machine-readable data formats that are commonly used by web APIs, described in the previous Learning Lunch.

Almost every popular web API returns data in one of two formats: XML or JSON. These formats can be very confusing. They look very different from how you are probably used to thinking of data. XML and JSON are not like a spreadsheet. They are both very flexible specifications for representing almost any kind of data. Both involve nesting, so you can represent complex data with lots of levels.

For example, you can have a list of countries, and each country can have a list of cities, and and each city can have a list of neighborhoods. Or think of a family tree, which can be represented easily enough in XML or JSON. You want to track some information about each person (e.g. their date of birth), but also their relationship to everything else. Every time you try to express complex nested relationships like these in a single two-dimensional table, an angel loses its wings.

A note on whitespace: In my examples, I indent things and put them on separate lines in order to make it clear what is inside what, but this is just for clarity. You can get rid of all this whitespace and put everything on one long line and it won’t change anything. Often, when you encounter data in the wild, like via an API, everything will be compressed onto one line with no whitespace. This is efficient but makes it harder to read. You can always dump it into a tool that will make it more readable, like this one.

The basics: XML

If you’ve ever worked with HTML, you understand the general idea behind XML too. Elements are defined by tags. Each element has a name and consists of an opening tag and a closing tag (these are expressed as <tagname> and </tagname>, respectively). Anything in between those two tags belongs to that element. It is the “parent” element of whatever is between the opening and closing tags. Those things in between are its “children.” Anything that is next to it, neither its parent nor its child, is its “sibling.”

<country>

<city>

<neighborhood>

</neighborhood>

<neighborhood>

</neighborhood>

</city>

<city>

<neighborhood>

</neighborhood>

</city>

</country>

In this example, you have a country with two cities in it. The first city has two neighborhoods in it, the second city only has one. So far this isn’t very helpful, because we haven’t specified WHICH country and cities we’re talking about. We can do that by adding attributes, which go inside the opening tag:

<country name="United States" population="311591917">

<city name="New York" population="8336697">

<neighborhood name="East Village">

</neighborhood>

<neighborhood name="Harlem">

</neighborhood>

</city>

<city name="Los Angeles" name="3819702">

<neighborhood name="Hollywood">

</neighborhood>

</city>

</country>

Now each element has attributes. We know the population of the country, the population of the cities, and the names of everything. We could add as many attributes as we want. The tag name tells you what type of thing an element is, and the attributes tell you details about it.

When you have a list of similar things in XML, you’ll typically see a list of siblings like those two cities, one after the next.

<country>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

</country>

Sometimes you’ll see a list like that enclosed in some sort of container element, like this:

<country>

<cities>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

<city></city>

</cities>

</country>

But it’s not required. When you have individual bits of data about an element (text, numbers, a date, that sort of thing), you can put it in attributes, but you can also make it the content of a tag. These are largely equivalent:

<city name="Los Angeles"></city>

<city>

<name>Los Angeles</name>

</city>

Reasons vary as to why someone might want to do it one way vs. the other when creating XML. If you use an attribute, you’re not supposed to have a second attribute of the same name. The value of an attribute is only supposed to be simple text and numbers, so you can’t nest things inside of it. While both examples above work for expressing that the city has the name “Los Angeles”, if you had a city inside a country, or a city with multiple name variations, that would be a problem:

This is OK:

<country>

<city name="Los Angeles"></city>

</country>

This is NOT OK:

<country city="<city name="Los Angeles"></city>">

</country>

This is OK:

<city>

<name>Los Angeles</name>

<name>LA</name>

</city>

This is NOT OK:

<city name="Los Angeles" name="LA">

</name>

A note on self-closing tags: You will also sometimes see an opening tag with no matching closing tag and a slash at the end instead, like this:

<city name="Los Angeles" />

This is just a shorthand way of declaring an element with nothing else inside.

These are equivalent:

<city name="Los Angeles"></city>

<city name="Los Angeles" />

To sum up, when looking at an XML document, you need to understand:

- An XML file is a hierarchy of elements.

- Elements are made up of an opening and closing tag and whatever is in between. In between it can have simple text and numbers, other elements, or both (or nothing).

- The opening tag of an element can also have attributes in the format

name="value". Each value should be simple text and numbers, not other elements.

A note on data types: a common question for people trying to learn about XML and JSON is how to store some special type of data, like a date or a time. XML and JSON don’t generally have a special way of dealing with things like this. You store them as text or numbers just like anything else, hopefully using some consistent format, like “10/18/2012” or “October 8, 2012” and then deal with parsing that later as needed.

The basics: JSON

JSON is a little trickier than XML unless you have some experience with JavaScript. JSON is a format largely made up of arrays and objects. When something is surrounded by [] square brackets, it’s an array. When something is surrounded by {} curly braces, it’s an object.

Arrays

An array is a list of items in order, separated by commas, like this:

["New York","Los Angeles","Chicago","Miami"]

New York is first, Miami is last. It’s OK if you don’t care about the order, just remember that it exists. Items in an array can be a bit of data (like text or a number), but they can also be objects or other arrays.

[["New York","Los Angeles","Chicago"],["Florence","Venice","Rome"]]

That list that is two items long. The first item is another list, of three US cities. The second item is also a list, of three Italian cities.

[{"name":"New York"},{"name":"Los Angeles"},{"name":"Chicago"}]

Don’t worry about the details of that list just yet, but just notice that it’s a list of three items, and each item is an object.

An array is a list, but it can have only one item, or zero items. These are both perfectly valid arrays:

[]

["Just one item"]

Objects

Objects also look like lists of things, but you shouldn’t think of them as lists. Each item is called a property and it has both a name and a value. The name is always enclosed in double quotes. Each one should only occur once in an object. They’re similar to attributes in an XML opening tag.

This is OK:

{

"name": "Los Angeles",

"population": 3819702

}

This is NOT OK:

{

"name": "Los Angeles",

"name": "LA",

"population": 3819702

}

Like an array, the value can be simple text or numbers, but it can also be an array or another object. So to fix the above example, you could do this:

{

"names": ["Los Angeles","LA"],

"population": 3819702

}

Two more examples:

{

"name": "United States",

"cities": ["New York","Los Angeles","Chicago"]

}

{

"name": "United States",

"leaders": {

"president": "Barack Obama",

"vicePresident": "Joe Biden"

}

}

Note on property names: you can use spaces in your property names if you really want to, like “vice president”, but you should avoid it. “vicePresident” or “vice_president” would be better, because if the data is going to end up used in code later, the spaces can be problematic.

An array is used for expressing a flat list of things (like sibling elements in XML), and an object is used for expressing specific details about one thing (like element attributes in XML).

I could, for example, use an object to list cities, but because each property requires a name, I’d have to specify an arbitrary unique name for each entry:

{

"city1": "Los Angeles",

"city2": "New York",

"city3": "Chicago"

}

In the interest of flexibility, I would rather use an array. That way, I can more easily add and subtract items. It’s also easier to use code later to find out how many cities are in the list or do something to them in order.

{

"cities": ["New York","Los Angeles","Chicago"]

}

The opposite is also true. I could use an array for a list of properties:

["Los Angeles","California",3819702]

I can use that as long as I remember that the first item in the list is the name of the city, the second item is the state it’s in, and the third item is the city’s population. But why bother? Using an object is better, because these are unique properties about the city. An object is more descriptive. If I need to add or remove properties, it’s much easier:

{

"name": "Los Angeles",

"state": "California",

"population": 3819702

}

Once you grasp those twin concepts, JSON will make a lot more sense.

- Arrays are for flat lists of things. They have a size and a sequence. If you can have more than one instance of a thing, you want an array.

- Objects are for unique descriptive details about something; the properties are written out like a list, but don’t think of them as a list. Think of an object like a profile.

JSON is made up entirely of those two kinds of nesting: objects and arrays. Each object can have other objects or arrays as values. Each array can have other arrays or objects as items in the list.

[

{

"name": "United States",

"population": 311591917,

"cities": [

{

"name": "New York",

"population": 8336697

},

{

"name": "Los Angeles",

"population": 3819702

}

]

},

{

"name": "Italy",

"population": 60626442,

"cities": [

{

"name": "Rome",

"population": 2777979

},

{

"name": "Florence",

"population": 357318

}

]

},

]

This is an array, a list with two objects in it. Both objects represent countries. They have properties for the country name and population. Then they have a third property, “cities”, and its value is an array. That array contains two MORE objects, each representing a city with a name and population. It seems confusing, but it’s a pretty flexible, logical way to store this information once you wrap your head around it.

To sum up, when looking at JSON, you need to understand:

- An array is a flat list of values. Those values can be simple data, or they can be arrays or objects themselves.

- An object is a set of named properties describing something. Each one has a value, and that value can be simple data or it can be an array or an object itself.

Things to think about

If you have a choice between getting data as XML or JSON, get whichever you’re more comfortable with, unless the data is going to be plugged directly into a web application. If someone is going to power JavaScript with the data, you want JSON, which is very JavaScript-friendly.

Also keep in mind that there are often multiple perfectly reasonable ways to structure the same data. Whoever came up with the structure for the data you’re getting may have had any number of reasons for doing it the way they did. Just concentrate on understanding the structure of the data you’re looking at before doing anything else with it.

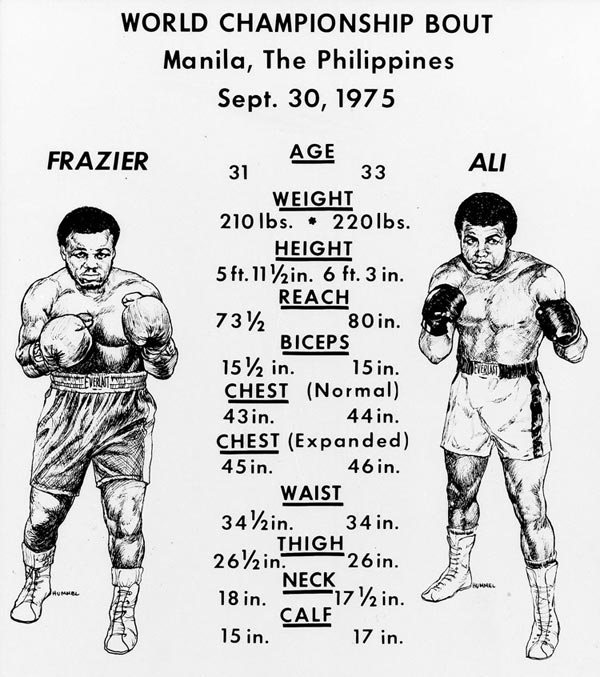

Example: The Thrilla in Manila

Boxing matches traditionally have something called “the tale of the tape,” which compares the physical characteristics of the two fighters. This is the tale of the tape for the 1975 Thrilla in Manila between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier:

Let’s look at how you might express a fighter’s characteristics in XML:

<fighter name="Joe Frazier">

<age>31</age>

<weight>210</weight>

<height>71.5</height>

<reach>73.5</reach>

<biceps>15.5</biceps>

<chest>

<normal>43</normal>

<expanded>45</expanded>

</chest>

<waist>34.5</waist>

<thigh>26.5</thigh>

<neck>18</neck>

<calf>15</calf>

</fighter>

You might want to specify units to be more helpful:

<fighter name="Joe Frazier">

<age>31</age>

<weight unit="pounds">210</weight>

<measurements unit="inches">

<height>71.5</height>

<reach>73.5</reach>

<biceps>15.5</biceps>

<chest>

<normal>43</normal>

<expanded>45</expanded>

</chest>

<waist>34.5</waist>

<thigh>26.5</thigh>

<neck>18</neck>

<calf>15</calf>

</measurements>

</fighter>

You could also put all the data into the <fighter> tag as attributes instead, as long as you collapse the two chest measurements:

<fighter name="Joe Frazier" age="31" weight="210" height="71.5" reach="73.5" biceps="15.5" chest-normal="43" chest-expanded="45" waist="34.5" thigh="26.5" neck="18" calf="15" />

In JSON, it might look like this:

{

"name": "Joe Frazier",

"age": 31,

"measurements": {

"weight": 210,

"height": 71.5,

"reach": 73.5,

"biceps": 15.5,

"chest": {

"normal": 43,

"expanded": 45

},

"waist": 34.5,

"thigh": 26.5,

"neck": 18,

"calf": 15

}

}

Now let’s imagine you want to express both fighters, along with some info about the fight itself:

<fight location="Manila, The Philippines" date="September 30, 1975">

<fighter name="Joe Frazier">

<age>31</age>

<weight unit="pounds">210</weight>

<measurements unit="inches">

<height>71.5</height>

<reach>73.5</reach>

<biceps>15.5</biceps>

<chest>

<normal>43</normal>

<expanded>45</expanded>

</chest>

<waist>34.5</waist>

<thigh>26.5</thigh>

<neck>18</neck>

<calf>15</calf>

</measurements>

</fighter>

<fighter name="Muhammad Ali">

<age>33</age>

<weight unit="pounds">220</weight>

<measurements unit="inches">

<height>75</height>

<reach>80</reach>

<biceps>15</biceps>

<chest>

<normal>44</normal>

<expanded>46</expanded>

</chest>

<waist>34</waist>

<thigh>26</thigh>

<neck>17.5</neck>

<calf>17</calf>

</measurements>

</fighter>

</fight>

In JSON, it might look like this:

{

"location": "Manila, The Philippines",

"date": "September 30, 1975",

"fighters": [

{

"name": "Joe Frazier",

"nicknames": [

"Smokin' Joe"

],

"hometown": "Philadelphia, PA",

"age": 31,

"weight": 210,

"measurements": {

"height": 71.5,

"reach": 73.5,

"biceps": 15.5,

"chest": {

"normal": 43,

"expanded": 45

},

"waist": 34.5,

"thigh": 26.5,

"neck": 18,

"calf": 15

}

},

{

"name": "Muhammad Ali",

"nicknames": [

"The Louisville Lip",

"The Greatest"

],

"hometown": "Louisville, KY",

"age": 33,

"weight": 220,

"measurements": {

"height": 75,

"reach": 80,

"biceps": 15,

"chest": {

"normal": 44,

"expanded": 46

},

"waist": 34,

"thigh": 26,

"neck": 17.5,

"calf": 17

}

}

]

}

Notice that the fight has three properties: the location, the date, and the fighters. The value of “fighters” is an array (a list) with two items. Each of those items is itself an object describing the individual fighter’s characteristics. Most of that data is just a number, but, for example, “nicknames” is an array because a boxer can have any number of nicknames. If you knew every boxer would have exactly one nickname, you wouldn’t need to make that an array.

Creating XML & JSON

This primer is mostly designed for you to loosely understand the structure of XML & JSON. Being able to create XML or JSON requires a more detailed and nitpicky understanding of the syntax. In the meantime, if you have tabular data (e.g. an Excel file), and you want to turn it into XML or JSON, or you just want to see what it looks like as XML/JSON for learning purposes, Mr. Data Converter is a great resource.