Rethinking data literacy: how useful is your 2-day training?

As of July 2017, School of Data’s network includes 14 organisations around the world which collectively participate to organise hundreds of data literacy events every year. The success of this network-based strategy did not come naturally: we had to rethink and move away from our MOOC-like strategy in 2013 in order to be more relevant to the journalists and civil society organisations we intend to reach.

In 2016 we did the same for our actual events.

The downside of short-term events

Prominent civic tech members have long complained about the ineffectiveness of hackathons to build long-lasting solutions for the problems they intended to tackle. Yet various reasons have kept the hackathon popular: it’s short-term, can produce decent-looking prototypes, and is well-known even beyond civic tech circles.

The above stays true for the data literacy movement and its most common short-term events: meetups, data and drinks, one-day trainings, two-day workshops… they’re easy to run, fund and promote: what’s not to love?

Well, we’ve never really been satisfied with the outcomes we saw of these events, especially for our flagship programme, the Fellowship, which we monitor very closely and aim to improve every year. Following several rounds of surveys and interviews with members of the School of Data network, we were able to pinpoint the issue: our expectations and the actual value of these events are mismatched, leading us not to take critical actions that would multiply the value of these events.

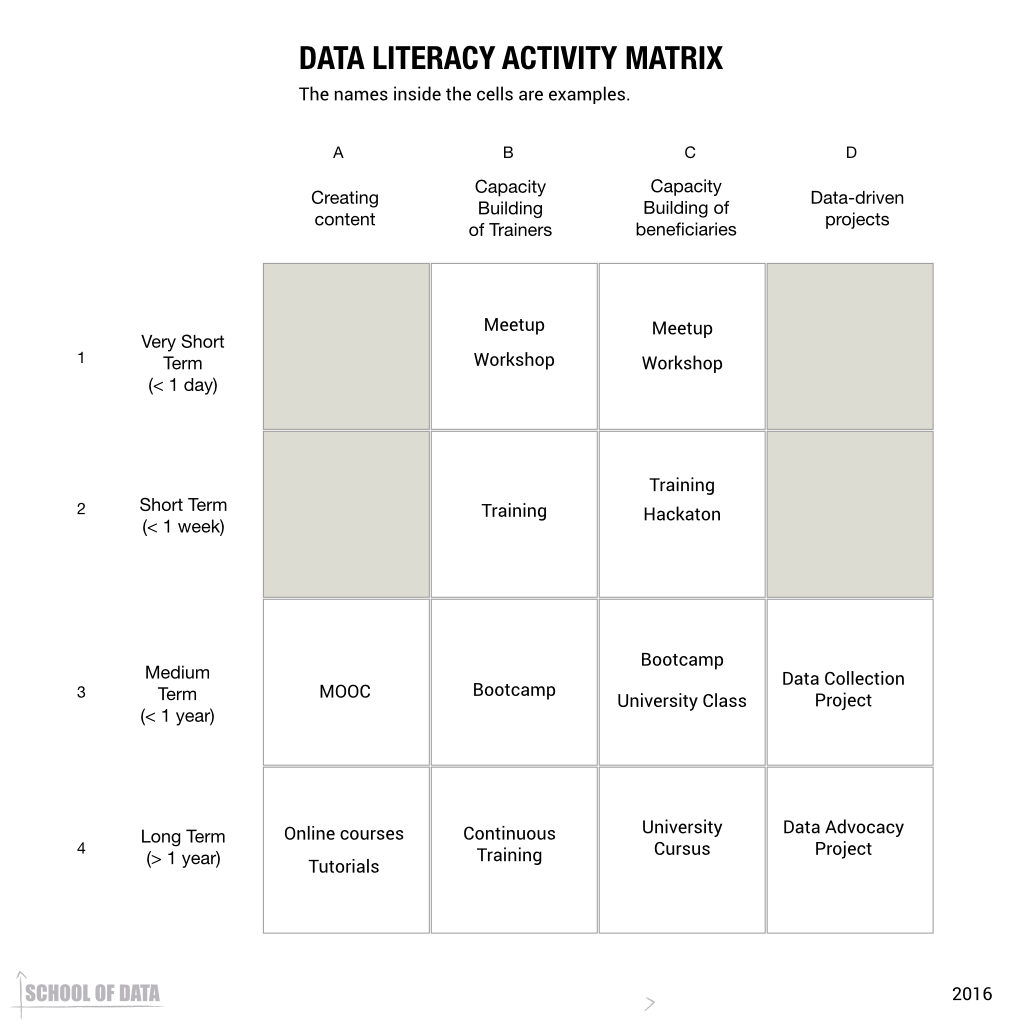

The Data Literacy Activity Matrix

To clarify our findings, we put the most common interventions (not all of them are events, strictly speaking) in a matrix, highlighting our key finding that duration is a crucial variable. And this makes sense for several reasons:

- Fewer people can participate in a longer event, but those who can are generally more committed to the event’s goals

-

Longer events have much more time to develop their content and explore the nuances of it

-

Especially in the field of data literacy, which is focused on capacity building, time and repetition are key to positive outcomes

(the categories used to group event formats are based on our current thinking of what makes a data literacy leader: it underpins the design of our Fellowship programme.)

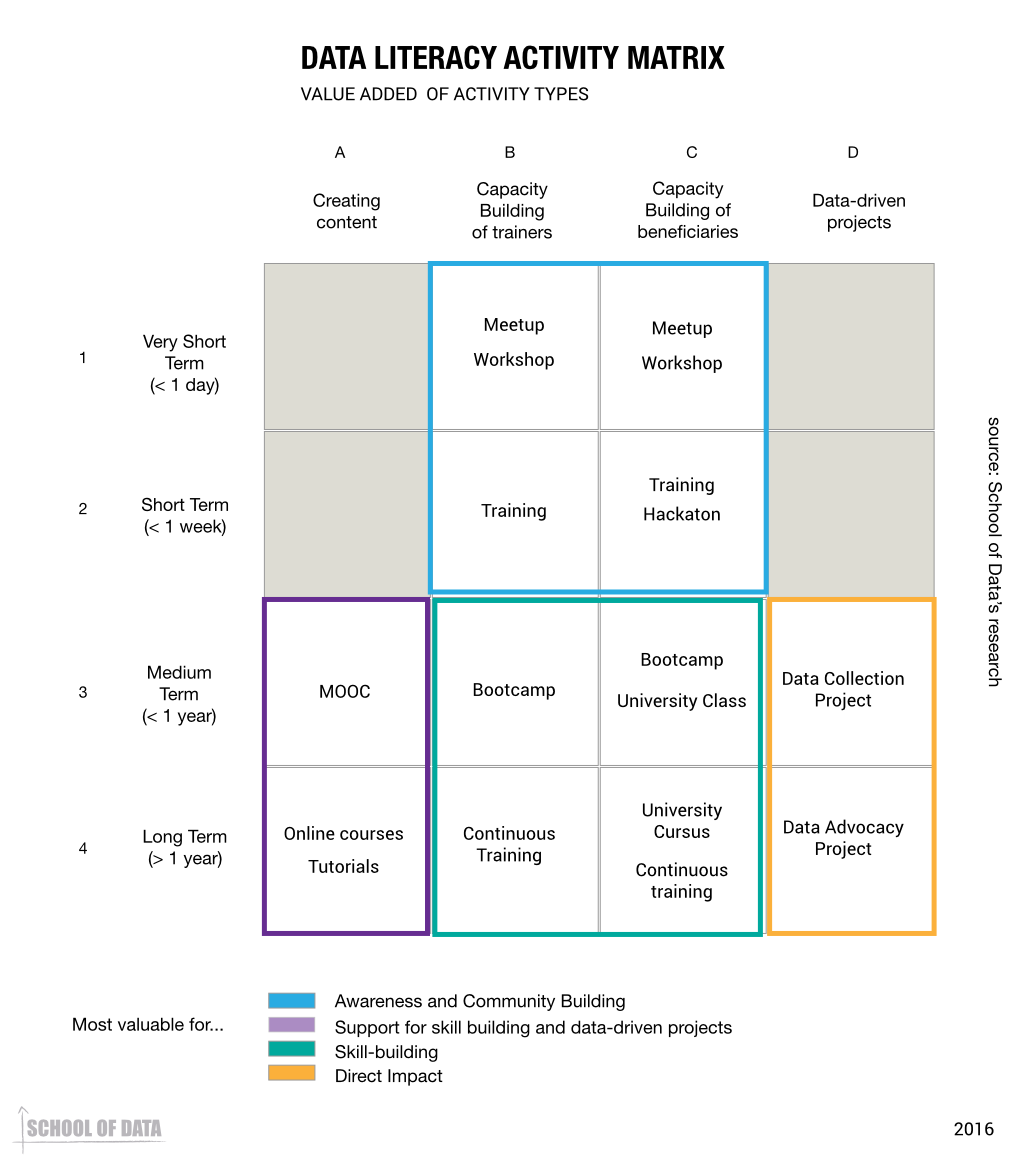

Useful for what?

The matrix allowed us to think critically about the added value of each subcategory of intervention. What is the effective impact of an organisation doing mostly short-term training events compared to another one focusing on long-term content creation? Drawing again from the interviews we’ve done and some analysis of the rare post-intervention surveys and reports we could access (another weakness of the field), we came to the following conclusions:

- very short-term and short-term activities are mostly valuable for awareness-raising and community-building.

-

real skill-building happens through medium to long-term interventions

-

content creation is best focused on supporting skill-building interventions and data-driven projects (rather than hoping that people come to your content and learn by themselves)

-

data-driven projects (run in collaboration with your beneficiaries) are the ones creating the clearest impact (but not necessarily the longest lasting).

It is important, though, not to set short-term and long-term interventions in opposition. Not only can the difference be fuzzy (a long term intervention can be a series of regular, linked, short term events, for example) but both play roles of critical importance: who is going to apply to a data training if people are not aware of the importance of data? Conversely, recognising the specific added value of each intervention requires also to act in consequence: we advise against organising short-term events without establishing a community engagement strategy to sustain the event’s momentum.

In hindsight, all of the above may sound obvious. But it mostly is relevant from the perspective of the beneficiary. Coming from the point of the view of the organisation running a data literacy programme, the benefit/cost is defined differently.

For example, short-term interventions are a great way to find one’s audience, get new trainers to find their voice, and generate press cheaply. Meanwhile, long-term interventions are costly and their outcomes are harder to measure: is it really worth it to focus on training only 10 people for several months, when the same financial investment can bring hundreds of people to one-day workshops? Even when the organisation can see the benefits, their funders may not. In a field where sustainability is still a complicated issue many organisations face, long-term actions are not a priority.

Next steps

School of Data has taken steps to apply these learnings to its programmes.

- The Curriculum programme, which initially focused on the production and maintenance of online content available on our website has been expanded to include offline trainings during our annual event, the Summer Camp, and online skillshares throughout the year;

-

Our recommendations to members regarding their interventions systematically refer to the data literacy matrix in order for them to understand the added value of their work;

-

Our Data Expert programme has been designed to include both data-driven project work and medium-term training of beneficiaries, differentiating it further from straightforward consultancy work.

We have also identified three directions in which we can research this topic further:

-

Mapping existing interventions: the number, variety and quality of data literacy interventions is increasing every year, but so far no effort has been made to map them, in order to identify the strengths and gaps of the field.

-

Investigating individual subgroups: the matrix is a good starting point for interrogating best practices and concrete outcomes in each of the subgroups, in order to provide more granular recommendations to the actors of the field and the designing of new intervention models.

-

Exploring thematic relevance: the audience, goals and constraints of, say, data journalism interventions, differ substantially from those of the interventions undertaken within the extractives data community. Further research would be useful to see how they differ to develop topic-relevant recommendations.