Using public data to flag tax avoidance schemes?

This post was jointly written by Jonathan Gray (@jwyg), Director of Policy and Ideas at the Open Knowledge Foundation and Tony Hirst (@psychemedia), Data Storyteller at the Open Knowledge Foundation’s School of Data project.

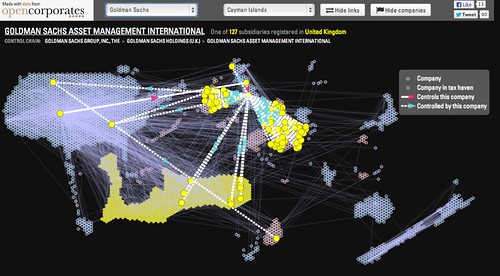

Today OpenCorporates added a new visualisation tool that enables you to explore the global corporate networks of the six biggest banks in the US.

The visualisation shows relationships between companies that are members of large corporate groups.

You can hover over a particular company within a corporate group to highlight its links with other companies that either control or are controlled by the highlighted company. It also shows which companies are located in countries commonly held to be tax havens.

As well as corporate ownership data, OpenCorporates also publishes a growing amount of information detailing company directorships. Mining this data can offer a complementary picture of corporate groupings.

The Offshore Leaks Database from The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, released earlier this year, also contains information about “122,000 offshore companies or trusts, nearly 12,000 intermediaries …, and about 130,000 records on the people and agents who run, own, benefit from or hide behind offshore companies”.

As you may have seen, we’ve recently been thinking about how all of this publicly available information about corporate ownership networks might be used to help identify potential tax avoidance schemes.

While the visualisation that OpenCorporates released today focuses on six corporate networks, we’d be interested in seeing whether we might be able to mine bigger public data sources to detect some of the most common tax avoidance schemes.

As more and more corporate data becomes openly available, might we be able to identify patterns within corporate groupings that could be indicative of tax avoidance schemes? What might these patterns look like? To what extent might you be able to use algorithms to flag certain corporate groupings for further attention? And to what extent are others (auditors, national tax authorities, or international fraud or corruption agencies) already using algorithmic techniques to assist with the detection of such arrangements?

There are several reasons that using open data and publicly available algorithms to detect potential tax avoidance schemes could be interesting.

Firstly, as tax avoidance is a matter of public concern arguably civil society organisations, journalists and citizens should be able to explore, understand and investigate potential avoidance, not just auditors and tax authorities.

Secondly, we might get a sense of how prevalent and widespread particular tax avoidance schemes are. Not just amongst high profile companies that have been in the public spotlight, but amongst the many other tens of millions of companies and corporate groupings that are publicly listed. The combination of automated flagging and collaborative investigations around publicly available data could be a very powerful one.

If you’re interested in looking into how data on corporate groupings might be used to flag possible tax avoidance schemes, then you can join us on the School of Data discussion list.