Ten Cool Things I Learned at DataJConf

Yan Naung Oak - August 18, 2017 in Events, Fellowship

This article was cross-posted from its original location at the Open and Shut blog

I had a fantastic time at the European Computational and Data Journalism Conference in Dublin on 6-7 July in the company of many like-minded data journalists, academics, and open data practitioners. There were a lot of stimulating ideas shared during the presentations on the first day, the unconference on the second day, and the many casual conversations in between!

In this post I’d like to share the ten ideas that stuck with me the most (it was tough to whittle it down to just ten!). Hopefully you’ll find these thoughts interesting, and hopefully they’ll spark some worthwhile discussions about data journalism and storytelling.

I’d really love to hear what you have to say about all of this, so please do share any thoughts or observations that you might have below the line!

The European Data and Computational Journalism Conference, Dublin, 6-7 July 2017

- ‘Deeper’ data journalism is making a real impact

Marianne Bouchart – manager of the Data Journalism Awards – gave a presentation introducing some of the most exciting award winners of 2017, and talked about some of the most important new trends in data journalism today. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the electoral rollercoasters of the past year, a lot of great data journalism has been centred around electioneering and other political dramas.

Marianne said that “impact” was the theme that ran through the best pieces produced last year, and she really stressed the central role that investigative journalism needs to play in producing strong data-driven stories. She said that impactful investigative journalism is increasingly merging with data journalism, as we saw in projects shedding light on shady anti-transparency moves by Brazilian politicians, investigating the asset-hoarding of Serbian politicians, and exposing irresponsible police handling of sexual assault cases in Canada.

- Machine learning could bring a revolution in data journalism

Two academics presented on the latest approaches to computational journalism – journalism that applies machine learning techniques to dig into a story.

Marcel Broersma from the University of Groningen presented on an automated analysis of politicians’ use of social media. The algorithm analysed 80,000 tweets from Dutch, British and Belgian politicians to identify patterns of what he called the ‘triangle of political communication’ between politicians, journalists, and citizens.

The project wasn’t without its difficulties, though – algorithmically detecting sarcasm still remained a challenge, and the limited demographics of Twitter users meant that this kind of research could only look at how narrow certain segments of society communicated.

Jennifer Stark from the University of Maryland looked at the possibilities for algorithms to be biased – specifically looking at Google Image Search’s representations of presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s photos during their campaigns. Through the use of an image recognition API that detects emotions, she found that Clinton’s pictures were biased towards showing her appear happier whereas for Trump, both happiness and anger were overrepresented.

Although it’s still early days for computational journalism, talks like these hinted at exciting new data journalism methods to come!

- There are loads of ways to learn new skills!

The conference was held at the beautiful University College Dublin, where a brand new master’s program in data journalism is being launched this year. We also heard from one of the conference organisers, Martin Chorley, about Cardiff University’s Master’s in Computational and Data Journalism, which has been going strong for three years, and has had a great track record of placing students into employment.

But formal education isn’t the only way to get those cutting edge data journo skills! One of the conference organisers also presented the results of a worldwide survey of data journalists, taking in responses from 180 data journalists across 44 countries. One of the study’ most notable findings was that only half of respondents had formal training in data journalism – the rest picked up the necessary skills all by themselves. Also, when asked how they wanted to further their skills, more respondents said they wanted to brush up on their skills in short courses rather than going back to school full-time.

- Want good government data? Be smart (and be charming)!

One of the most fascinating parts of the conference for me was learning about the different ways data journalists obtained data for their projects.

Kathryn Tourney from The Detail in Northern Ireland found Freedom of Information requests useful, but with the caveat that you really needed to know the precise structure of the data you are requesting in order to get the best data. Kathryn would conduct prior research on the exact schemas of government databases and work to get hold of the forms that the government used to collect the data she wanted before making the actual FOI requests. This ensured that there was no ambiguity about what she’d receive on the other side!

Conor Ryan from Ireland’s RTÉ found that he didn’t need to make FOI requests to do deep investigative work, because there was already a lot of government data “available” to the public. The catch was that this data was often buried behind paywalls and multiple layers of bureaucracy.

Conor stressed the importance of ensuring that any data sources RTÉ managed to wrangle were also made available in a more accessible way for future users. One example related to accessing building registry data in Ireland, where originally a €5 fee existed for every request made. Conor and his team pointed out this obstacle to the authorities and persuaded them to change the rules so that the data would be available in bulk in the future.

Lastly, during the unconference one story from Bulgaria really resonated with my own experiences trying to get a hold of data from governments in closed societies. A group of techies offered the Bulgarian government help with an array of technical issues, and by building relationships with staff on the ground – as well as getting the buy-in of political decision makers – they were able to get their hands on a great deal of data that would have forever remained inaccessible if they’d gone through the ‘standard’ channels for accessing public information.

- The ethics of data sharing are tricky

The best moments at these conferences are the ones that make you go: “Hmm… I never thought about it that way before!”. During Conor Ryan’s presentation, he really emphasized the need for data journalists to consider the ethics of sharing the data that they have gathered or analysed.

He pointed out that there’s a big difference between analysing data internally and reporting on a selected set of verifiable results, and publishing the entire dataset from your analysis publicly. In the latter case, every single row of data becomes a potential defamation suit waiting to happen. This is especially true when the dataset involved is disaggregated down the level of individuals!

- Collaboration is everything

Being a open data practitioner means that my dream scenarios are collaborations on data-driven projects between techies, journalists and civil society groups. So it was really inspiring to hear Megan Lucero talk about how The Bureau Local (at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism) has built up a community of civic techies, local journalists, and civil society groups across the UK.

Even though The Bureau Local was only set up a few months ago, they quickly galvanized this community around the 2017 UK general elections, and launched four different collaborative investigative data journalism projects. One example is their piece on targeted ads during the election campaign, where they collaborated with the civic tech group Who Targets Me to collect and analyse data about the kinds of political ads targeting social media users.

I’d love to see more experiments like The Bureau Local emerging in other countries as well! In fact, one of the main purposes of Open and Shut is precisely to build this kind of community for folks in closed societies who want to collaborate on data-driven investigations. So please get involved!

Who Targets Me? Is an initiative working to collect and analyse data about the kinds of political ads targeting social media users.

- Data journalism needs cash – so where can we find it?

It goes without saying these days that journalism is having a bad time of it at the moment. Advertising and subscription revenues don’t pull in nearly as much cash as the used to. Given that pioneering data-driven investigative journalism takes a lot of time and effort, the question that naturally arises is: “where do we get the money for all this?”. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no-one at DataJConf had any straightforward answers to this question.

A lot of casual conversations in between sessions drifted onto the topic of funding for data journalism, and lots of people seemed worried that innovative work in the field is currently too dependent on funding from foundations. That being said, attendees also shared stories about interesting funding experiments being undertaken around the world, with the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism’s crowdfunding approach gaining some interest.

- Has data journalism been failing us?

In the era of “fake news” and “alternative facts”, a recurring topic in many conversations was about whether data journalism actually had any serious positive impacts. During the unconference discussions, some of us ended up being sucked into the black hole question of “What constitutes proper journalism anyway?”. It wasn’t all despair and navel-gazing, however, and we definitely identified a few concrete things that could be improved.

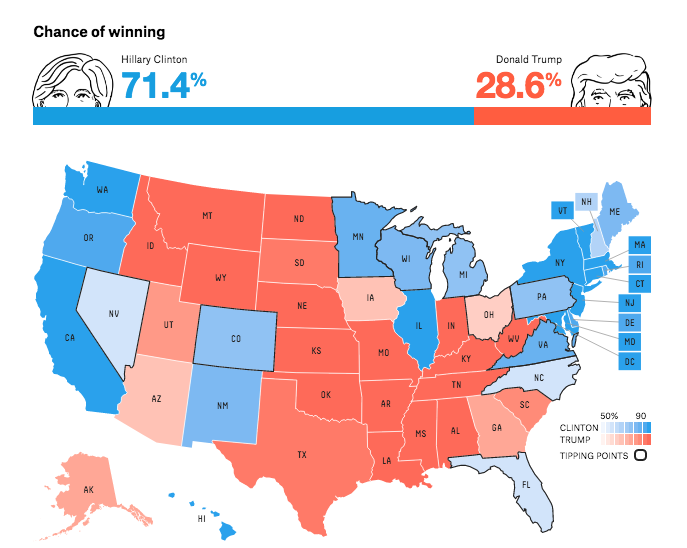

One related to the need to better represent uncertainty in data journalism. This ties into questions of improving the public’s data literacy, but also of traditional journalism’s tendency to present attention-grabbing leads and conclusions without doing enough to convey complexity and nuance. People kept referencing FiveThirtyEight’s election prediction page, which contained a sophisticated representation of the uncertainty in their modelling, but hid it all below the fold – an editorial decision, it was argued, that lulled readers into thinking that the big number that they saw at the top of the page was the only thing that mattered.

FiveThirtyEight’s forecast of the 2016 US elections showed a lot of details below the fold about their forecasting model’s uncertainty, but most readers just looked at the big percentages at the top.

Another challenge identified by attendees was that an enormous amount of resources were being deployed to preach to the choir instead of reaching out to a broader base of readers. The unconference participants pointed out that a lot of the sophisticated data journalism stories written in the run-up to the 2016 US elections were geared towards partisan audiences. We agreed that we needed to see more accessible, impactful data stories that were not so mired in party politics, such as ProPublica’s insightful piece on rising US maternal mortality rates.

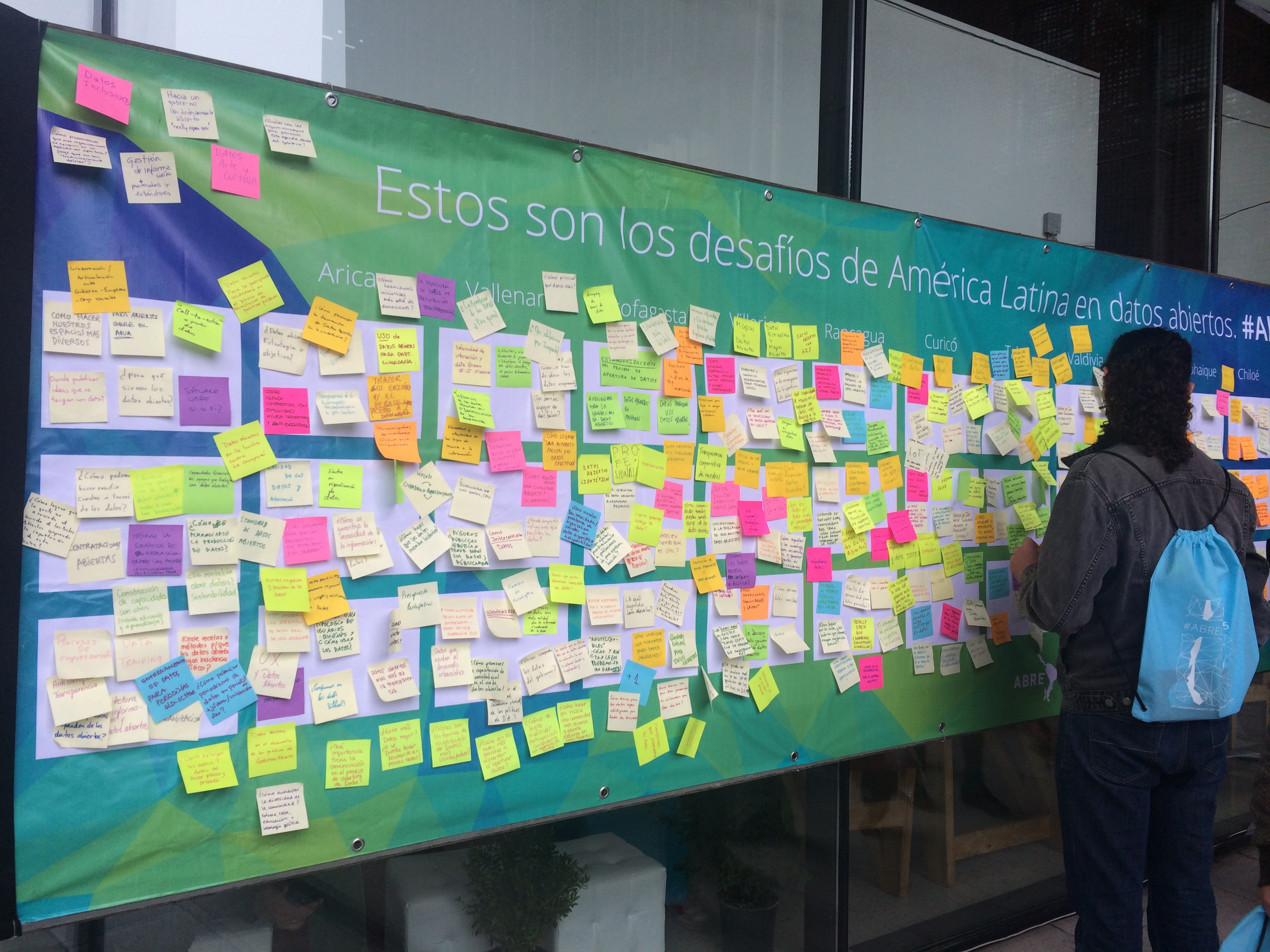

- Data journalism can be incredibly powerful in the Global South

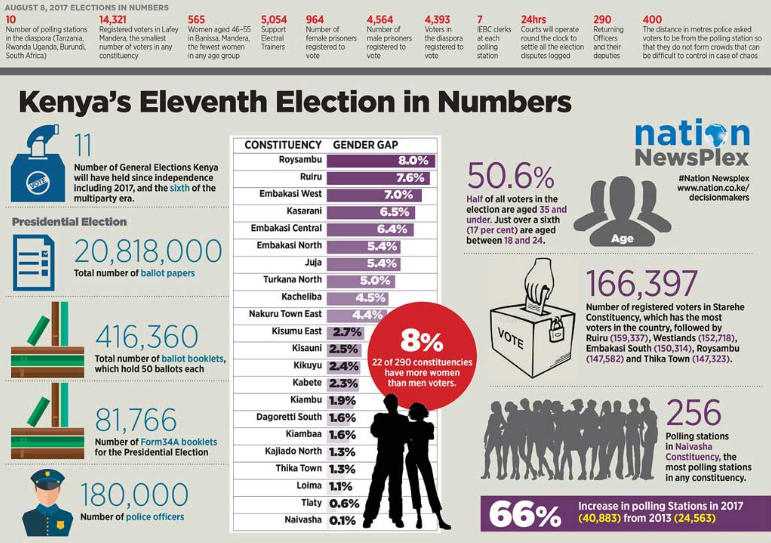

Many of the talks were about data journalism as it was practised in Western countries – with one notable exception. Eva Constantaras, who trains investigative data journalism teams in the Global South, held a wonderful presentation about the impactfulness of data journalism in the developing world. She gave the examples of IndiaSpend in India and The Nation in Kenya, and spoke about how their data-driven stories worked to identify problems that resonated with the public, and explain them in an accessible and impactful way.

Election coverage in these two examples shared by Eva focused on investigating the consequences of the policy proposals of politicians, engaging in fact-checking, and identifying the kinds of problems that were faced by voters in reality.

Without the burden of partisan echo-chambers, and because data journalism is still very new and novel in many parts of the world, data journalism could end up having a huge impact on public debate and storytelling in the Global South. Watch this space!

Kenya’s The Nation has been producing data-driven stories more and more frequently, such as this piece on Kenya’s Eleventh Elections in August 2017*

- Storytelling has to connect on a human level

If there was one recurring theme that I heard throughout the conference about what makes data journalism impactful, it was that the data-driven story has to connect on a human level. Eva had a slide in her talk with a quote from John Steinbeck about what makes a good story:

“If a story is not about the hearer he [or she] will not listen… A great lasting story is about everyone, or it will not last. The strange and foreign is not interesting – only the deeply personal and familiar.”

“I want loads of money” — Councillor Hugh McElvaney caught on hidden camera video from RTÉ

Conor from RTÉ also drove the same point home. After his team’s extensive data-driven investigative work revealed corruption in Irish politics, the actual story that they broke involved a hidden-camera video of an undercover interview with one of these politicians. This video highlighted just one datapoint in a very visceral way, which ultimately resonated more with the audience than any kind of data visualisation could.

I could go on for longer, but that’s probably quite enough for one blog post! Thanks for reading this far, and I hope you managed to gain some nice insights from my experiences at DataJConf. It was a fascinating couple of days, and I’m looking forward to building upon all of these exciting new ideas in the months ahead! If any of these thoughts have got you excited, curious (or maybe even furious) we’d love to hear from you below the line.

Open & Shut is a project from the Small Media team. Small Media are an organisation working to support freedom of information in closed societies, and are behind the portal Iran Open Dat*a.