Jargon busting the world of aid

Zara Rahman - February 2, 2015 in

This is intended more as a reference point while you’re working through the Aid Data curriculum, rather than to be read or worked through from start to finish. Each specialist term, in bold, is listed in the glossary, and has two sections: its definition, and an explanation of why it might be relevant while you’re working with aid data.

If you come across other terms you think should be added, let us know!

Module Objectives:

- Get familiar with some common words you’ll see while looking into aid data

Prerequisites/before you get started:

- None!

Table of Contents:

- Organisations and institutions to be aware of

-

General development terms

-

Aid + financial flow terms

-

Further resources

Introduction

We’ve talked about the accessibility of data, but what about the accessibility of language? As with many sectors, international development is full of acronyms and complex terms which might have different meanings to those you’re used to.

This module isn’t intended to be read from top to bottom, but rather to keep as a reference. Are there any you’d like to add? Suggest them on the School of Data mailing list, or tweet us

Inspiration for this glossary has been drawn heavily from others – wherever possible, we try to explain them in accessible language, and they are listed in the [Further Resources] section.

Content

Organisations/institutions to be aware of

G7 (previously, the G8): The Group of Eight is a forum of eight countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, United Kingdom and United States). Together, these eight countries represent about 14% of the world’s population, but about 60% of the world’s wealth. In March 2014, Russia was suspended from the group, in response to the country’s annexation of Crimea, leaving them as the G7. The group meet several times a year to discuss economic issues.

Data relevance: in 2013 the G8 released their ‘Open Data Charter’, pledging to ‘open’ more government data, and including the principle ‘Open Data by default’. If these pledges are implemented, there should be more data about these governments and their activities coming soon(ish.) Their actions against this charte**r will presumably be assessed at future G8 summits. The Open Data Charter is online to read here.

G20: The Group of Twenty (G20) is essentially a wider evolution of the G8, aiming to bring other nations into the economic discussions. It is relatively new, and held its first meeting in 2008. As with the G8, other non-member nations also attend meetings and summits, and some international institutions (eg. the UN, the African Union) also send delegations to attend the summits.

Data relevance: in 2009, the G20 launched their ‘Data Gaps’ initiative, which is a set of 20 recommendations on the enhancement of economics and financial statistics. One of the main outcomes is this “Principal Global Indicators” site, which brings together data for the G20 economies.

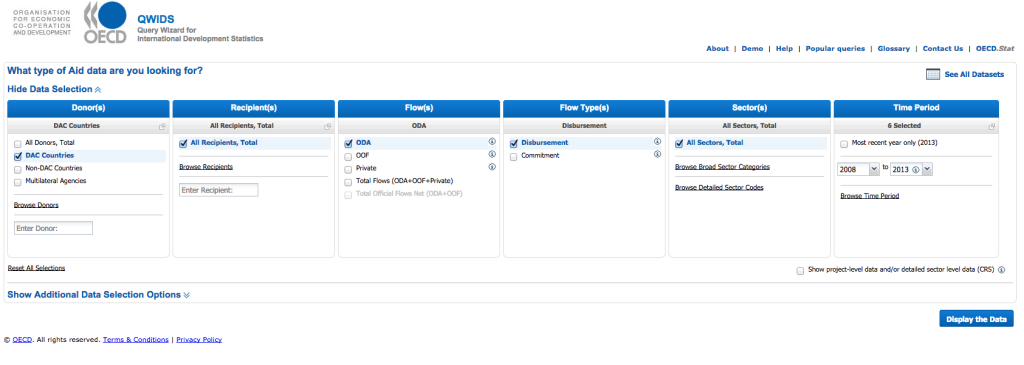

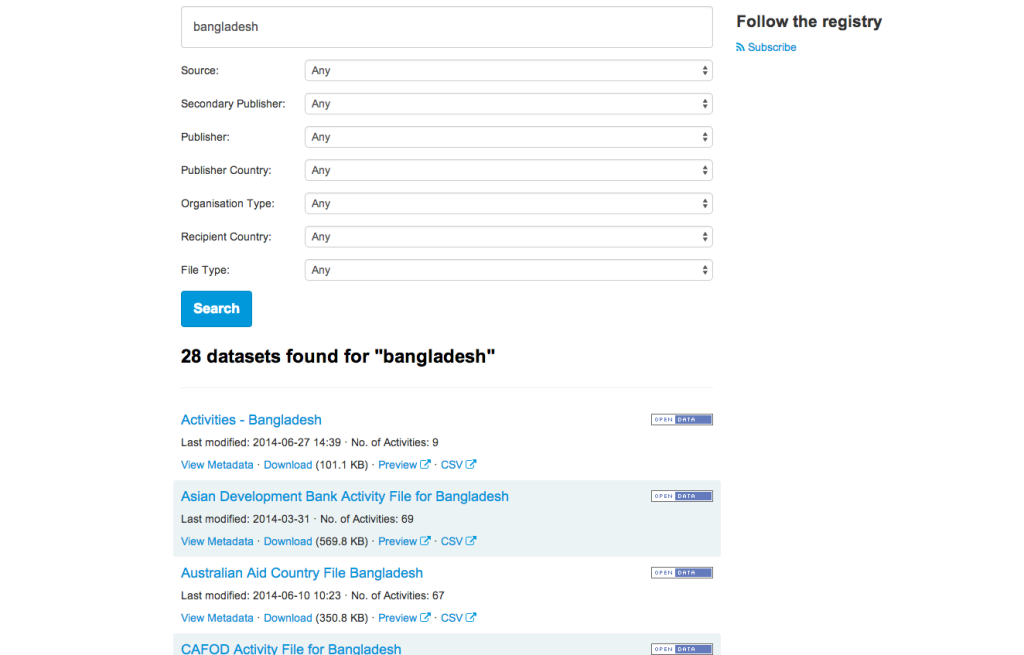

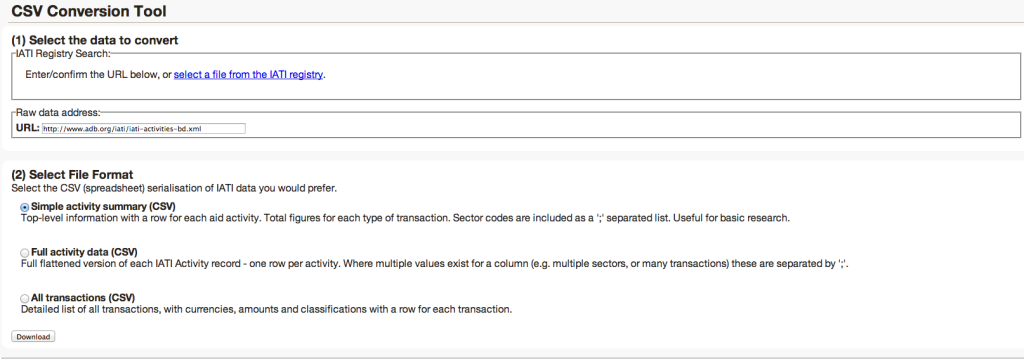

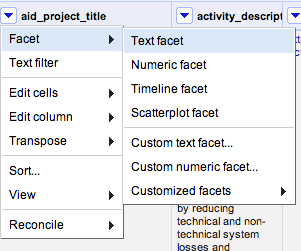

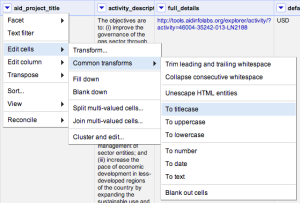

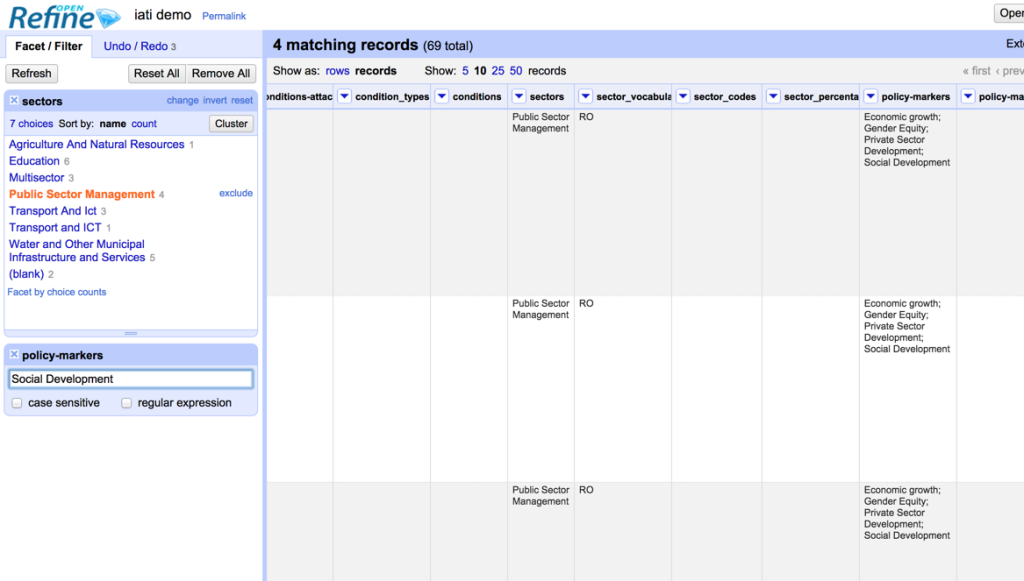

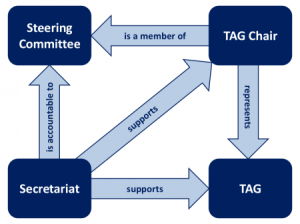

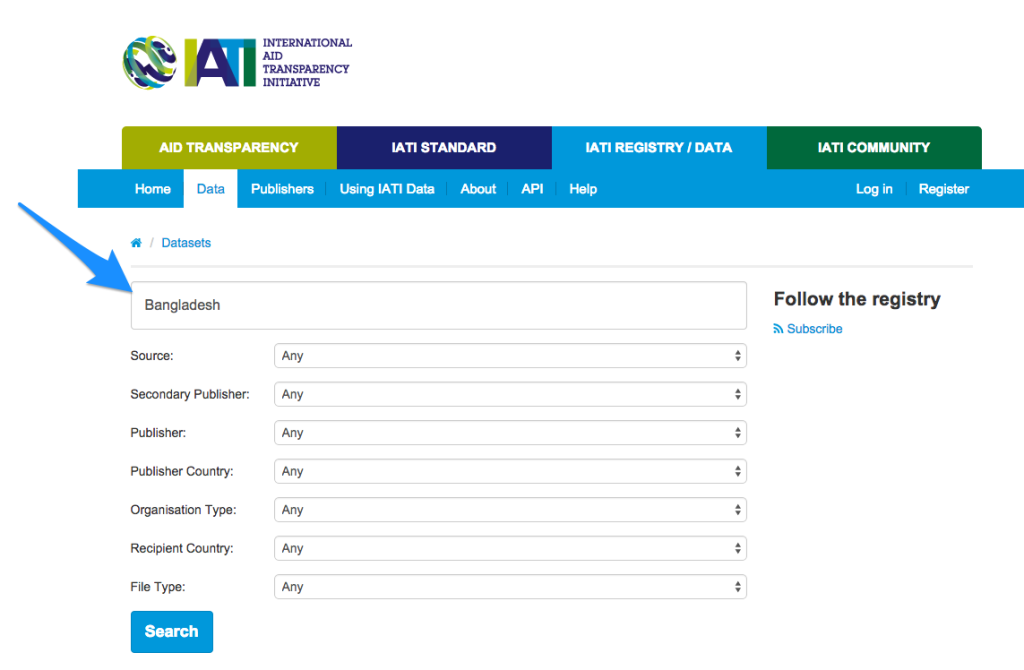

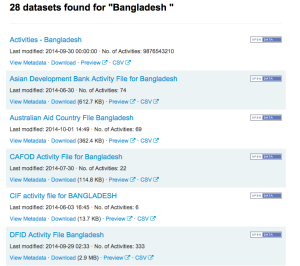

IATI – the International Aid Transparency Initiative – the largest global transparency initiative working on improving transparency of aid and development resources. It involves donors, recipient countries and civil society organisations, and they have developed a standard for publishing data – the IATI standard.

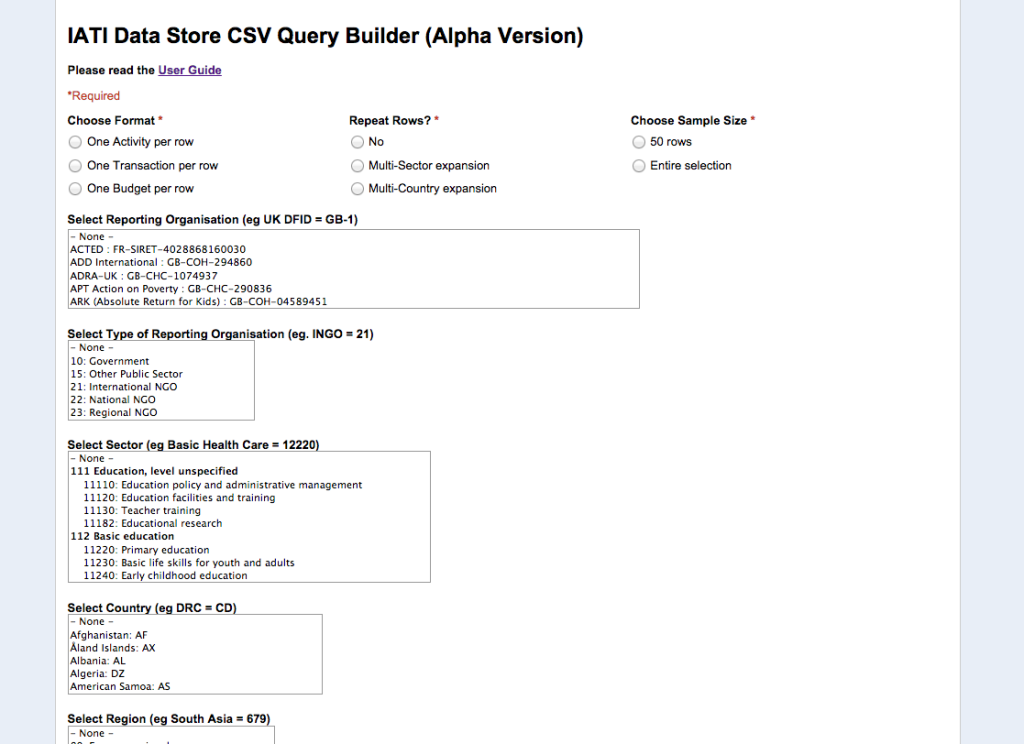

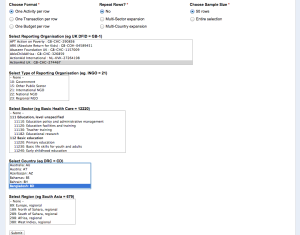

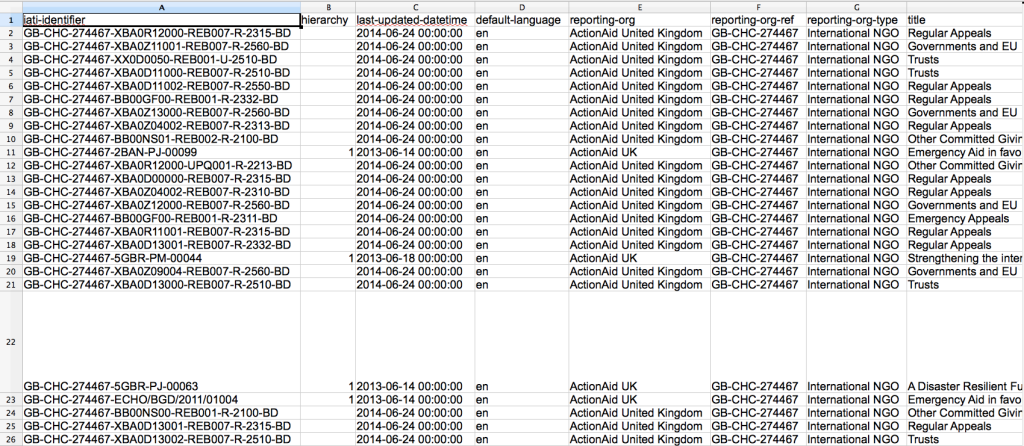

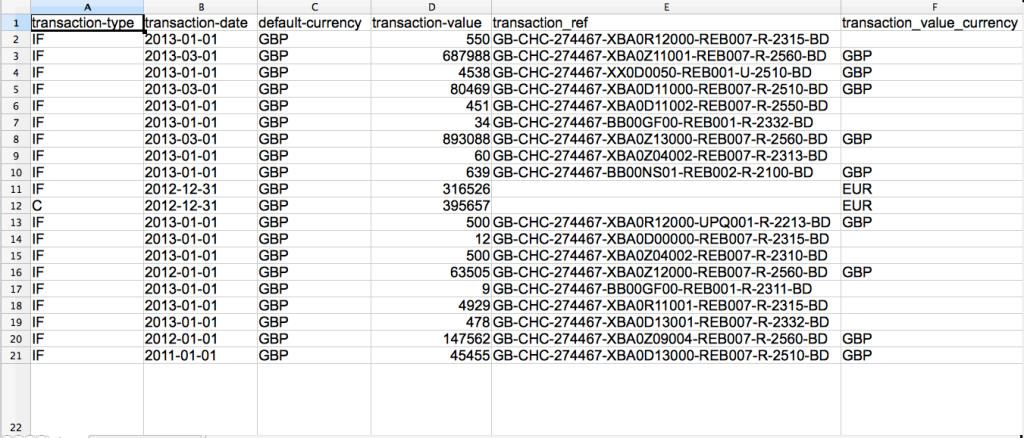

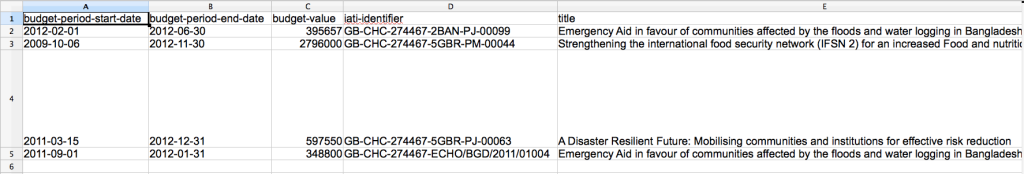

Data relevance: this is another major source of data about aid, though it’s difficult to know what has already been covered in OECD-DAC data (see above). Additionally, lots of major donors have committed to publishing their data to IATI – ie. via this standard – so the data in here will only improve. For more information, see module [A Guide to IATI data].

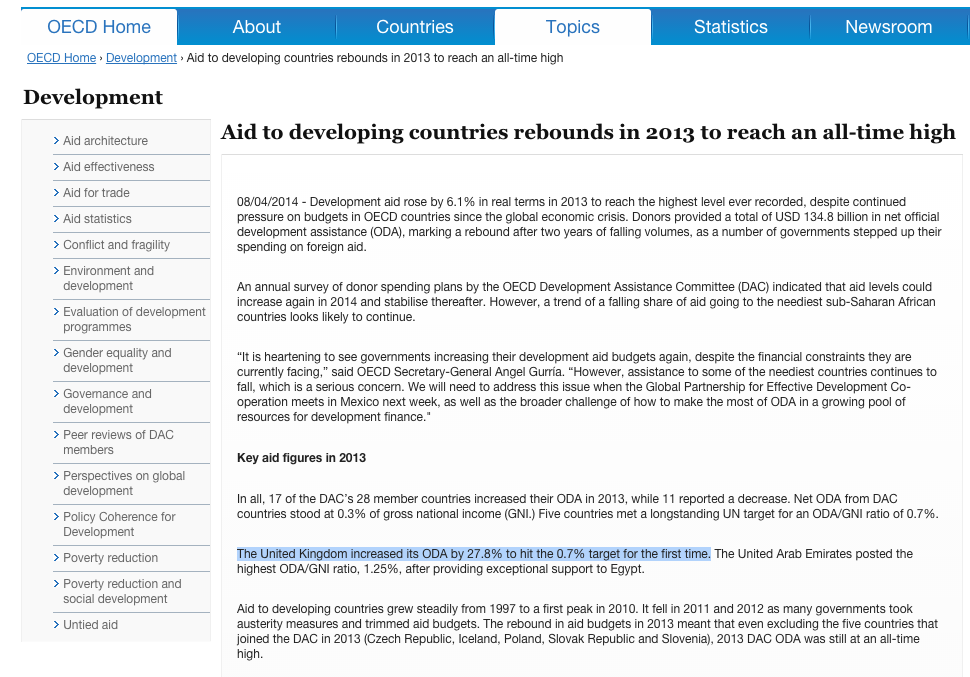

OECD – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, is an international economic organisation of 34 countries, founded in 1961. Most of these 34 countries are high-income countries. They work essentially through peer pressure, which occasionally leads to binding treaties between countries. Each year, they produce a number of publications, books and policy papers.

Data relevance: they are one of the biggest producers (and collectors) of data about the economic status of countries around the world. For more information on where to access this data, see module “A Guide to OECD data”.

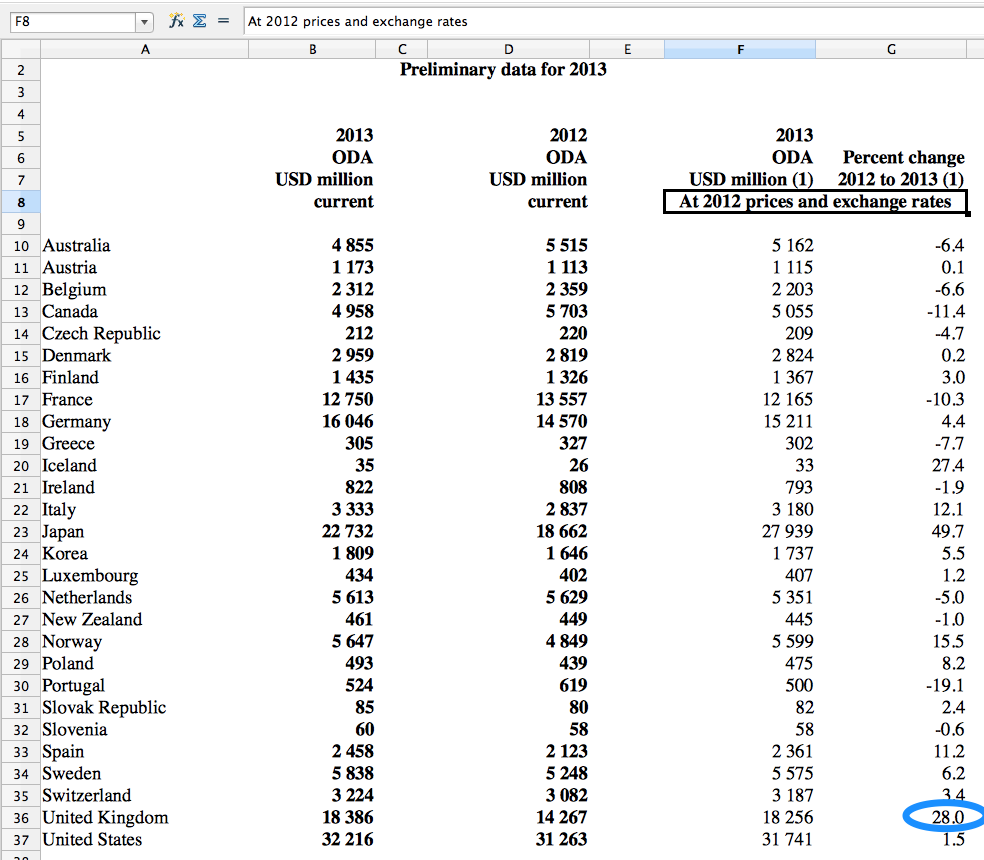

OECD-DAC: A sub-committee of the OECD, as described above – the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is made up of different countries which provide bilateral aid. Countries within the OECD can be ‘members’, and countries outside the OECD can apply to be ‘associates’.

Data relevance: they produce the most trusted and comprehensive sources of data on resource flows to developing countries – for more information on where to access this data, see module “A Guide to OECD data”.

General terms

GNI – Gross National Income – A term used to describe the total national income of a country. Essentially, it measures everything that nationals of a certain country are doing/producing – the output – whether they are living in that country or not. This differs from Gross Domestic Product, which measures the economic value of what is happening in that specific country by foreigners + nationals alike (but doesn’t count any activities happening outside the country.)

Data relevance: when you’re thinking about how ‘rich’ a country is, make sure you’re comparing similar statistics, as GNI can (in some cases) differ greatly from GDP)

Gross Domestic Product, GDP – A term used to measure a country’s economic productivity or national wealth, based purely on geographical location of production (ie. within the respective country).

Data relevance: this is often used as a measure of how ‘developed’ a country is – the higher the GDP (especially GDP per capita, or per person), the more developed the country.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – A set of eight international development goals officially established following the UN Millennium Summit in 2000, to be met by 2015. It looks like some goals will be met, and others won’t. The goals include poverty and hunger, education, gender equality and empowering women, child mortality, maternal health, HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, environmental sustainability and a global partnership for development.

Data relevance: the MDGs have been at the centre of the development agenda for almost the last 15 years. This means that measuring ‘progress’ in global development has largely been understood through the framework of measuring different areas against MDG indicators, and many are keen to use the data to display that as many goals as possible have been met. Keep an eye out for such claims, and wherever possible, have a look into the data behind these claims yourself. *

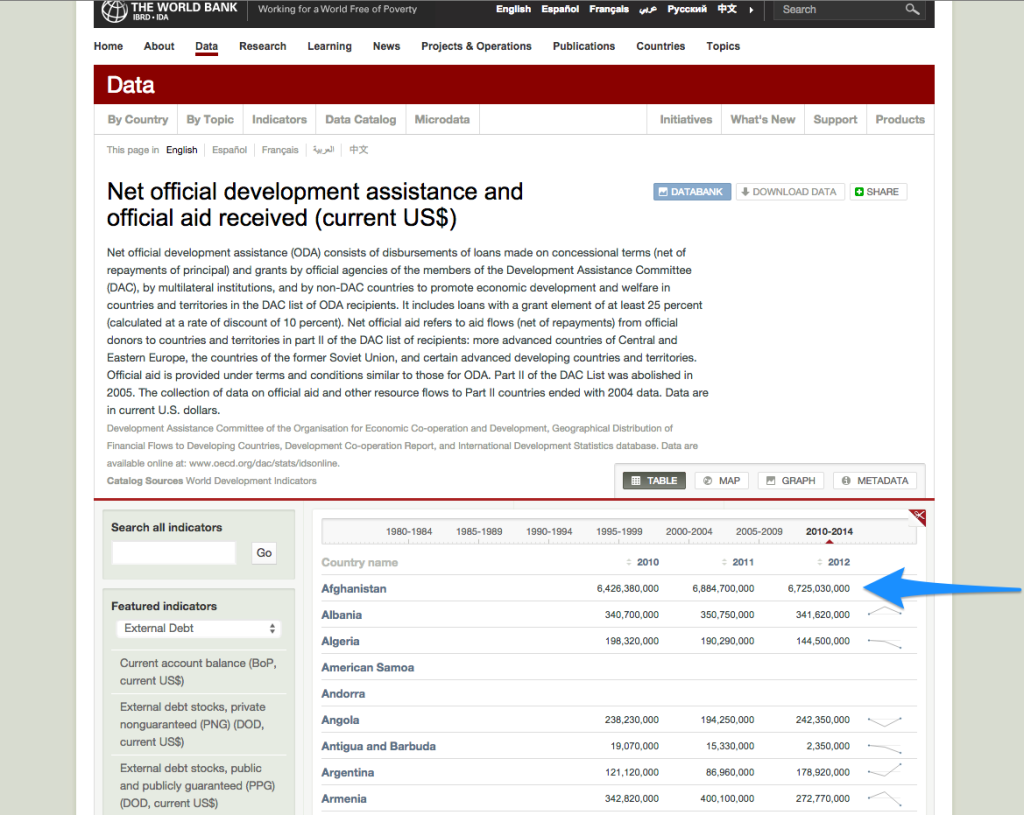

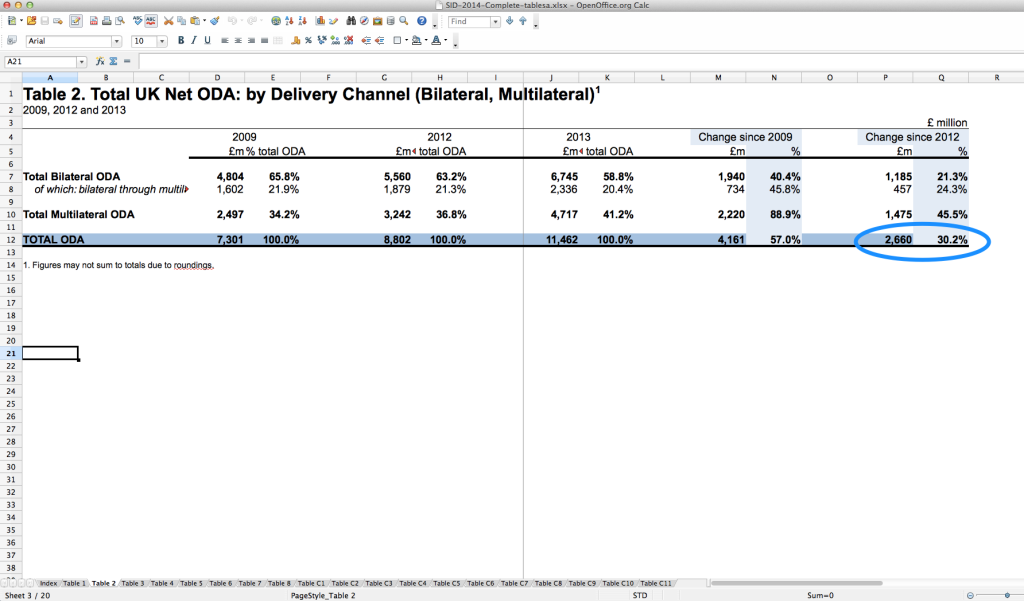

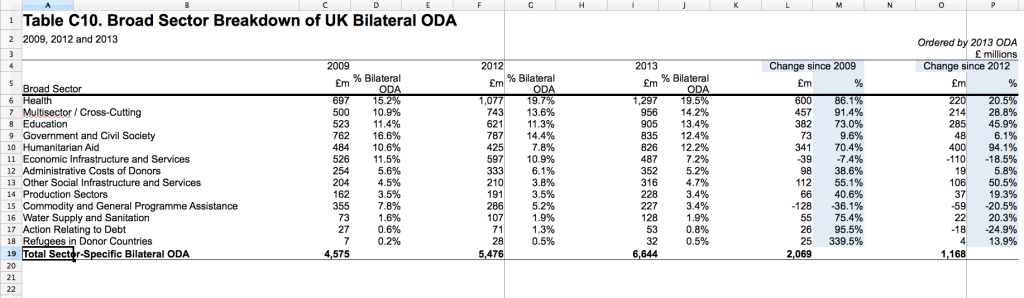

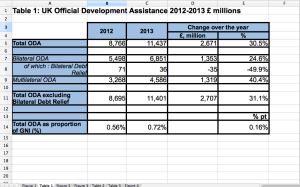

Official Development Assistance, (ODA): a grant or loan from a high-income country to a low-income country, with the aim of promoting economic development or welfare. Misleadingly, ODA does not always result in the actual transfer of money to the country “receiving” the ODA. It can be defined as debt relief, or technical cooperation, for example.

Read more:

*Fact sheet: Is it ODA? from the OECD, and a shorter description of what the OECD defines as ODA. (short definition) and longer fact sheet http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/34086975.pdf

Data relevance: ODA is the official, or more politically correct, term for what is sometimes termed “foreign aid”, and the amounts spent by high-income countries on ODA is wildly misunderstood by the public. Be aware of public (mis)perceptions around how much is spent, as well as representing ODA accurately when looking at financial flows between high- and low- income countries.

Sustainable Development Goals, SDGS – A set of goals which will supercede the Millennium Development Goals (see above), and are due to be set in September 2015. Work is ongoing in establishing these by a designated UN working group.

Data relevance: it’s likely that these will be the basis of the development agenda for the next 15 years or so. So it’s good to be aware that they are being set, but for now (December 2014) there is nothing specific to keep an eye out for.

Aid / financial flows

Aid bundle: aid comes in many forms: as money, as food, in the form of skilled people coming and offering their services (= technical consultancy), or even items that mean that the money never actually leaves the donor country, such as debt relief, or grants for students from poor countries to study in a more economically developed country.

Data relevance: the combination of the above items, and more, which make up the ‘aid bundle’ can differ greatly between recipient countries. Be aware that these differences can mean that some countries get a “better deal” than others, despite seemingly receiving a lower amount of money.

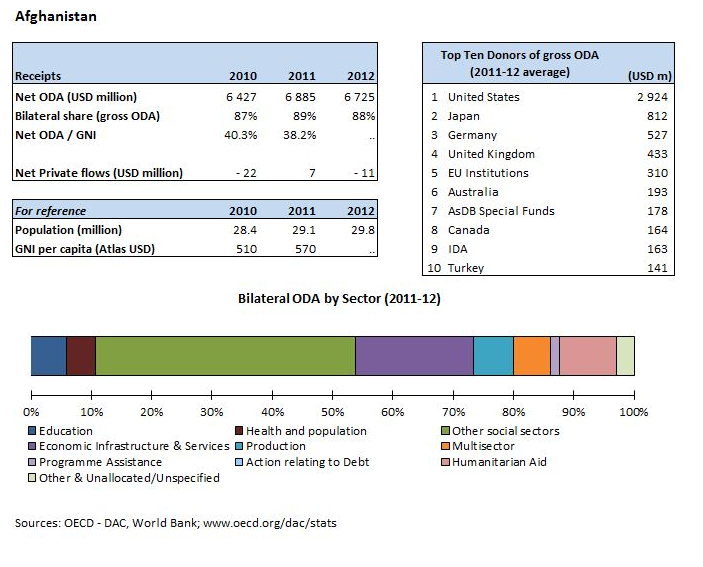

Bilateral aid – Aid given by the government of one country directly to another.

Data relevance: it can also reveal a lot about a country’s political interests, if they are supporting certain countries more than others.

Commitments: Firm, written obligations of what resources will be distributed within ODA — but crucially, this is not always the actual amount that gets distributed. (see: disbursements)

Data relevance: be careful whether you are looking at ‘commitments’ or ‘disbursements’ when looking at amounts spent within ODA. If you are looking at what a donor was planning on giving in a given year, you’ll want to look at commitments.

Concessional loans: Loans given from a high-income country to a low-income country, which can form part of ODA (see above). To qualify as ‘concessional’ loans, they must give the low-income country a better deal than usual loans – this can be either by giving them more time to pay the loan off, or by having a lower interest rate.

Data relevance: money provided through ‘concessional loans’ can, somewhat misleadingly, be classed as ‘official development assistance’, but it is important to note that no money is actually given to the low-income country, and that they actually have to pay it back. So, if a country is providing ODA largely in the form of concessional loans, they’re not really providing that much money to the recipient country, as they will (eventually) receive all of it back.

Development aid: aid, or official development assistance, aimed at alleviating poverty in the long term. Also described as ‘development cooperation’.

Data relevance: be sure to note the difference between ‘humanitarian aid’ and ‘development aid’ – as development aid is typically focused on long term response, it should be entirely possible to provide forward-looking, and timely data, both of which are crucial for low-income countries to be able to plan their budgets appropriately.

Disbursements: the actual amount of money, or resources, given within ODA.

Data relevance: this is most likely the most useful measurement for you of how much money a donor has actually given to a certain country.

Earmarked aid/funds: aid which is given with certain restrictions placed on how, or when, it is used; this can be anything from specifying what the money is used for, specified services, or the timeframe within which it must be used. [Opposite = ‘unearmarked aid’]

Data relevance: for the recipient country, receiving ‘earmarked funds’ might leave them with a lot less freedom than ‘unearmarked funds’ – this is simply a classification to be aware of, when looking into ODA and aid flows.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) A long-term investment from one country to another, where an entity based in one country has a ‘controlling’ ownership in a business enterprise in another.

Data relevance: this is not considered as ‘official development assistance’, but is in many cases far larger in amount than ODA flows from rich countries to poor countries, so it is good to be aware of it as a potential financial flow to low-income countries.

Humanitarian/emergency aid: typically provided in response to humanitarian crises or emergencies – such as natural or man-made disasters, with the primary objective of saving lives and alleviating suffering in the short term.

Data relevance: inherently, this is hard to predict, so forward-facing data cannot really be provided, as different donors’ responses differ depending on the particular situation in hand, and how it progresses over time.

Multilateral aid – Aid given from the government of a country to an international agency such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund or the United Nations, who are then charged with distributing it among low-income countries.

Data relevance: it is important to bear in mind that international agencies such as the ones listed above are not, though they may seem like it, ‘neutral’. Some – like the World Bank – are very heavily funded by just one country, which means that they are somewhat tied to the interests of that country. Be aware of this when thinking about projects funded by international agencies.

Remittances: A remittance is a transfer of money by a foreign worker to their home country.

Data relevance: Money sent home by migrants constitutes the second largest financial inflow into many developing countries, in some cases far exceeding international aid. When thinking about financial flows between countries, be careful to think about ‘unusual suspects’.

Tied Aid: Aid which has a restriction placed upon it so that it must be used by the recipient country to purchase products or services from the donor country. More information. Opposite: Untied Aid.

Data relevance: providing tied aid is a clear way for a high-income country to establish strong links between itself and the recipient country, whether this be for political, cultural or economic reasons. Either way, putting these restrictions on the aid means that, like with earmarked aid, the recipient country has less freedom to make decisions for themselves on what the resources are spent on (or rather, where).

Unearmarked aid/funds – where the recipient has complete freedom to decide how the money/resources are used (this is a condition for multilateral aid)

Further resources

Glossaries provided by other organisations:

From Development Initiatives, this Glossary