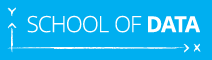

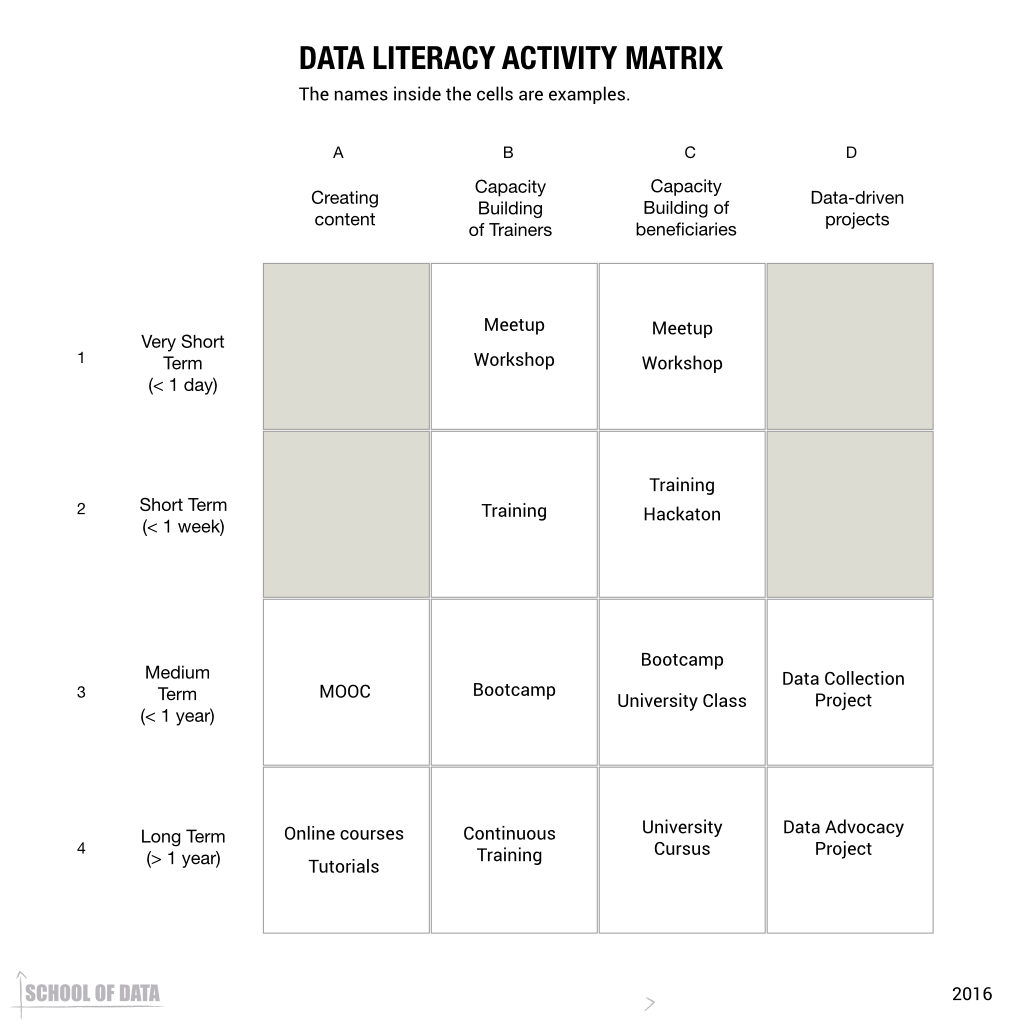

After exploring how to define data literacy, we wondered about the reality of the work of data literacy advocates. Which methodology do they use and what does it look like in practice? Unsurprisingly, there is a wide range of methodologies in use across different groups. Each of them fits the available opportunities, time and resources.

Short term efforts

Workshops

A large part of the training done by the data literacy advocates surveyed take the form of workshops. Participants agreed that workshops (rather than talks) were a good way to promote practical learning, and also the short timeframe allowed for the participation of individuals and organizations with resource constraints. Some workshops can be delivered inside of conferences and events (ranging from two hours to a half-day), and their learning goals are largely limited to introducing the basic topics to participants. Some of those workshops can be multi-day, ranging from two to five days: they allow for a longer exposure to processes and provide enough of a foundation to start concrete data projects. Multi-day workshops may also be augmented with follow-up sessions designed to provide guidance and support during the life of a data project.

The following short term workshops were mentioned:

- 2 hour workshops: they are the ones that take place in conferences, and which only provide space for an introduction (but require few resources to make happen)

- Half day workshops: they are seen as good for introductions to topics, as well as spaces to do practical work. For example: Data Therapy’s workshops.

- 2 to 3-day workshops: they provide enough practice time to make it feasible to start specific projects

- 5-day workshops: two of the organizations surveyed mentioned them as great opportunities to go through entire processes (like the data pipeline) with workshop participants

- 10-day workshops: the longest workshop format that was mentioned in interviews; they provide enough space to go through entire processes as well as work on specific projects from scratch.

The Data Pipeline

In regard to the content of these workshops, they often start with what participants described as “data basics” (what is data, what is data journalism, etc). After this introduction, it is common for trainers to explain the process of working with data. Here, a recurring concept is the School of Data pipeline, as shown in the illustration. It is a pedagogical device created to show that “data wrangling takes place in several stages; in order to process data, it must be moved through a ‘pipeline’. […] Raw data must usually travel through every stage of the pipeline – sometimes going through one stage more than once” (Newman, 2012). While the data pipeline is heavily promoted and used by the School of Data network, participants outside of the network were found to use the pipeline model to describe the type of content they cover in workshops.

Beside the data pipeline-like methodologies, another specific type of exercice that came up during the research was the “reverse engineering” of data exercises: deconstructing existing examples to explain how they came to be and make them more relatable for the trainees.

Community events

Along with workshops, community events have developed as a way to have a more social component to events, while getting informal but practical help and advice.

- Data clinics: those events provide space where people can develop their data skills, ask questions related to their own data and get help with challenges they are facing in their data projects

- Data meetups: many organizations that do trainings also devote resources to hosting informal meetups where people can share learnings on their own data projects, along with getting insights into other data projects.

Datathons

Another intensive format is the Datathon, which is based on the concept of hackathons. They are often named “data expeditions”, “data dives”, “data quests” and are popular with data literacy practitioners, along with individuals who have more established data-literacy skills. Quoting a participant, “acquiring data skills requires short, intensive bursts of focus from a group, rather than the type of attention you would have during 6-8 weeks with sessions that last a couple of hours per week”.

Medium term efforts

Some of the formats do not require individuals to be removed from their workplace. The training is brought to them, either physically at their workplace, or online, allowing participation from their place of work. The online format is generally conducted over a period of several weeks or months, a few hours a week.

- 5-week newslab model: in contexts where journalists cannot leave their newsroom, trainings can be brought to the newsroom.

- 4-week training: in opposition to the hypothesis that led to the birth of data expeditions, this model relies on a relatively modest demand of time each week, and relies on the accumulation of practice over four weeks.

- 1-week workshop with follow up: when there is interest in supporting a long term process, but offline training can’t be sustained over a long continuous period, follow up sessions can extend the process.

Some interviewees mentioned paying special attention to the need of developing communities of practice with alumni, in order to provide spaces where they can continue to develop expertise and learn from each other’s experiences.

Long term efforts

On the longer end of the scale, the long term efforts correspond to immersive endeavours where an individual is placed within a data project lasting anywhere from five months to a year. This takes the form of either fellowship programs, allowing an individual to gain expertise by being placed within a data project, or a mentorship program, where an individual with data expertise is placed within a data project to help build the skills of staff while working side by side.

- Fellowship programs: tend to last from 5 months to a year. Some participants favor fellowship programs for data journalists in environments where such intensive involvement is not disruptive to the media industry. School of Data has experience in this regard, too, with its own group of School of Data fellows.

- Research processes: some participants sustained long term capacity building through a research process that they documented. For communities that must collect and analyse their own data in the face of other challenges, such as marginalisation and illiteracy, an approach of a multi-year engagement towards empowerment can be successful. An example of this can be found in the FabRiders’ blog post series What we learned from Sex Workers.

- Six-month projects: rather than doing it through workshops, data literacy training can take place in the form of involvement in specific projects with the guidance of a mentor.

Online vs offline

Most of the aforementioned formats (except for the follow-up community) take place primarily offline regardless of the duration, but some online formats were brought up by participants – primarily by those whose native language isn’t English, and whose communities don’t have a wealth of data literacy resources in their language. Some mentioned MOOCs (one of the participants ran a five-week MOOC on data journalism – the first one ever in Portuguese, the language spoken in her country, Brazil); others, dedicated websites (one of the participants was prompted by the desire to introduce trends she admired in other contexts, while translating the resources that could aid in this adoption); webinars as an attempt to replicate brief offline trainings, and paying attention to social media content as a source of learning.

Choosing an effective format

Despite the wide range of formats that are used to help build data literacy, the selected format for an event often comes down to two factors: the availability of funding and the amount of time participants are willing to invest. In some contexts, journalists and/or activists can’t give up more than two days at a time; in others, they can give up to half a year. The least disruptive formats are chosen for each community. There is a noticeable difference in the types of actors and the engagements they will favor. Larger and older organizations favor intensive, long term processes with relatively few beneficiaries; smaller and younger organizations or individuals favor short-term trainings to reach larger audiences.

Interviewees focused on developing developing data literacy capacity in both individuals and organisations favor providing experiential, project-driven work. Often it’s about providing people with a dataset and getting them to develop a story from it; other times, it’s hands-on training on different parts of the data pipeline. Most interviewees so far have made an emphasis on the importance of providing opportunities for hands-on experience with data. They also strive for having concrete outcomes for their trainings where participants can see immediate impact of their work with data.

Curriculum Sources

The research participants mentioned several sources of inspiration around data literacy, which can be found below:

In our next post ‘Measuring the Impact of Data Literacy Efforts’ we will look at how data literacy practitioners measure and evaluate their methodologies and efforts.