10th November marks the 3 year anniversary of the very first data expedition. What have we learned in the last 3 years?

Anyone who followed School of Data closely in the early years knows that originally the focus of the project was online. This is the story of how and why the project moved away from prioritising its online offering to rely heavily on a network of humans to do the work. There are a diversity of views about the subject within the School of Data network, this is my take.

Musings about materials

Let’s talk for a second about why writing materials for data skills training is particularly tricky.

1. Tool volatility

You may be merrily using a tool one week and the next, it has been killed off. People were still grumbling about the loss of Needlebase several years later. Companies also change their offerings substantially

(e.g. ScraperWiki) and materials quickly went out of date. We couldn’t keep up.

I felt strongly that one of School of Data’s tasks was to make the world of data tools less overwhelming: to show that you could do a lot with only a few key tools. We picked some staples — easy tools you could do a lot with.

New tools and services are appearing every day. Many are old wine in new bottles — but some are very impressive. Evaluating when it makes sense to move from an old favourite to something new is time intensive in and of itself, let alone writing training materials for them.

2. Software discrepancies

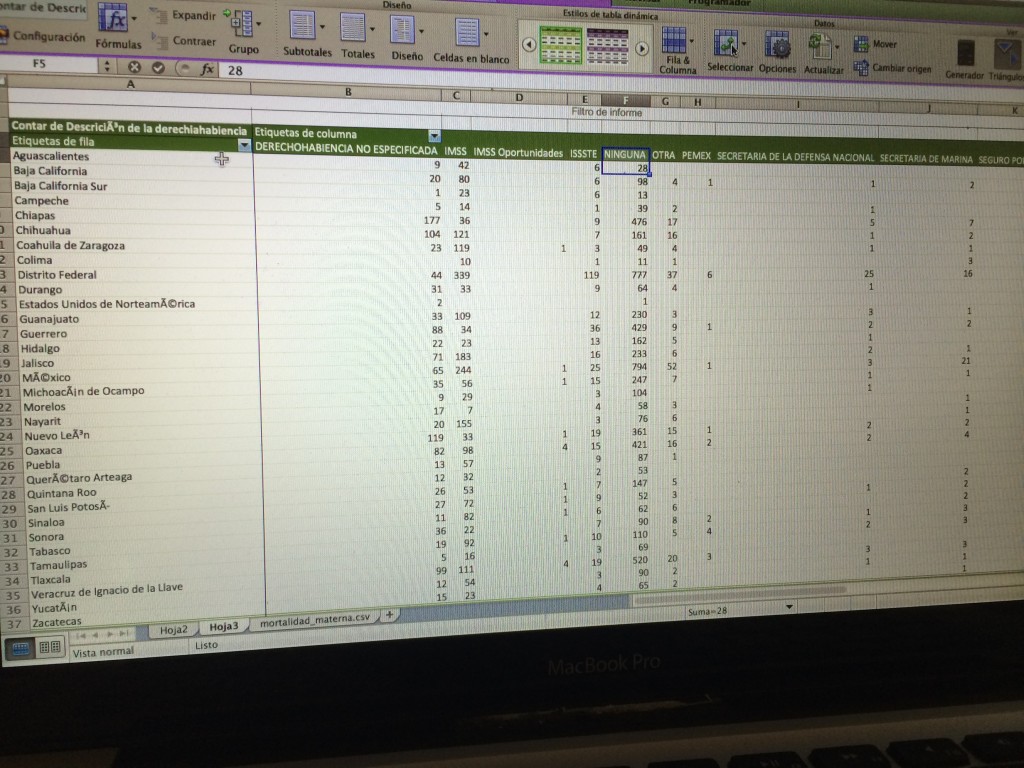

Through early user tests we discovered the diversity of software used for even basic tasks such as spreadsheets was very large. Even if we wrote a tutorial for one piece of software, e.g. LibreOffice, the differences between other versions of similar programmes e.g. Excel / GoogleDocs were just great enough to leave learners entirely stuck if they were using anything but the type we had written it for.

3. No two organisations ever want to do exactly the same thing

The direction of teaching materials falls somewhere on a spectrum between closely tailored to an individual use case and open ended general principles.

At one end: the handholding, instructive walkthrough.

Pros: Very easy to follow. Excellent for beginners.

Cons: Interesting for a very narrow audience. Doesn’t encourage the learner to think creatively about what they could do with those skills. Breaks very easily as soon as anything about the service you are using changes.

At the other end: general principles e.g. “mapping” (vs “using X tool to create maps” and open ended challenges.)

Pros: Don’t need updating as often. Encourage learners to think more broadly about how the skills they use could be applied.

Cons: There needs to be some way for the user to make the leap from general principle to concrete implementation.

When you are supporting organisations to find stories in data or use data to support their advocacy, no two organisations will ever have exactly the same questions. This makes it very hard to find a common set of materials for them.

4. The resource question $$$

Creating teaching materials for any topic is a lot of work. In the early days of School of Data, we were 2-3 people.

Don’t get me started on how much work it is to produce a MOOC. We dabbled in these for a while. I’ve personally taken part in some good ones and partners have had some success with them, but the problem for School of Data was that with our resourcing level, it would have been putting all of our eggs in one basket very early on in the project.

We needed more time and flexibility to experiment with different formats, to see what would work for our specific target audience.

5. The feedback problem

There was a feedback problem with online materials, we had no idea whether the people we were reaching with the online materials were the ones we were targeting. In the early days, we really only did workshops to get feedback for a more online approach. We got the best feedback from participants at test workshops we did in person. Feedback which we got through the website was sparse.

Then something happened…

Enter the dragon: the beginning of Data Expeditions

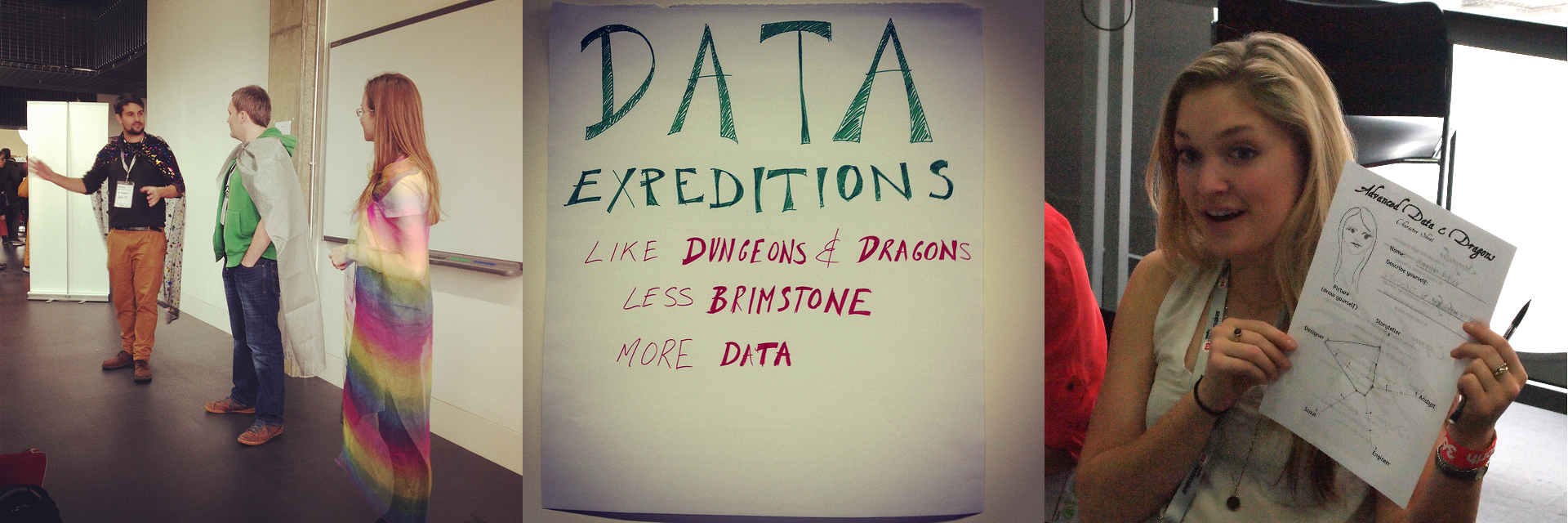

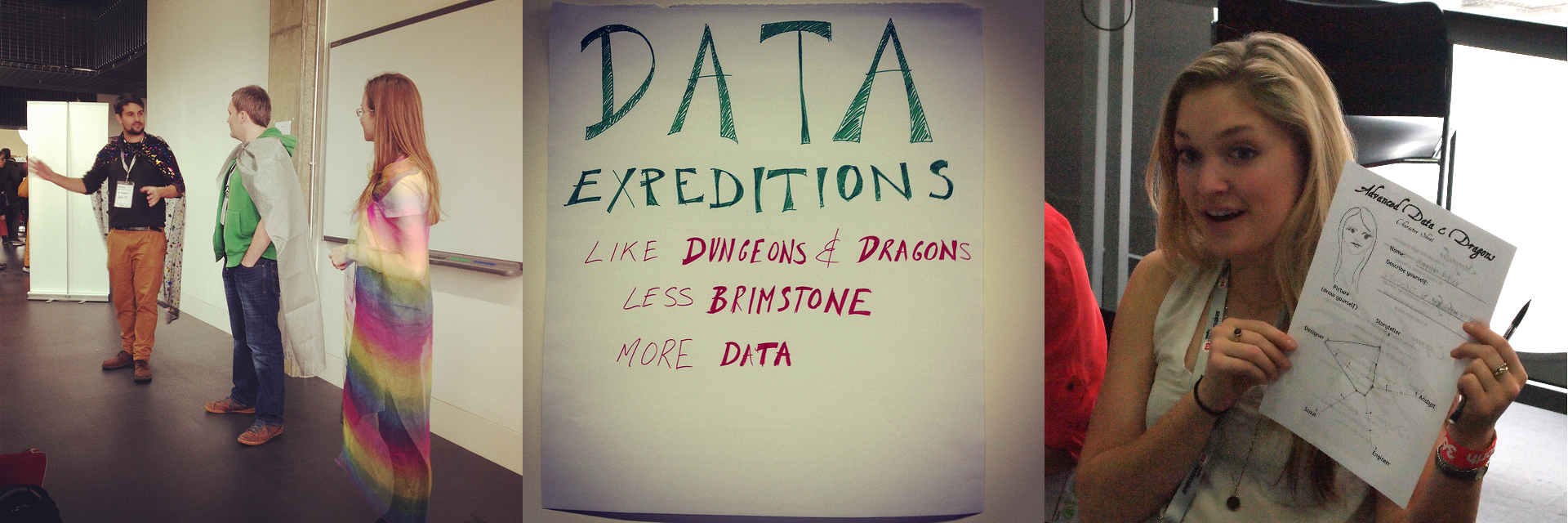

It’s 10th November 2012 and I’m surrounded by nerds in sparkly capes. This is Mozilla Festival (MozFest) — a playground for new ideas that have something to do with making use of the web in creative and fun ways.

A few months earlier (on the day of the MozFest submission deadline) my colleague, Friedrich (in the green hoodie and silver cape above) had lamented that it was really hard to teach investigative skills in an interesting way. Michael Bauer (star cape, far left), from the School of Data team, happened to be in town visiting.

We agree that we should try and find a way of including investigations in the session. A far cry from the carefully planned tutorials with perfectly aligned practice data, participants would get a taste of reality… In the wild, there is no-one to clean your datasets for you. What we needed now was a way to get other people to help each other through the mires and holes that the participants will inevitably find themselves in.

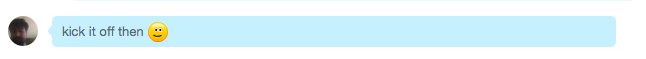

Friedrich and Michael start nerding-out about how cool it would be to model a session on Dungeons and Dragons. Confession: I to this day have never played D&D. Nevertheless, I catch enough of their gist to gather that it is some kind of role-playing game, and there are dragons — how wrong can it go?

We decide that if this idea is going to work anywhere, it’s going to be at MozFest, whose open minded guinea pigs — sorry, participants — are usually up for a laugh. We have a name, “Data Expeditions”, now we just have to work out how to facilitate a session with an unknown number of people, with unknown skillsets, and a mostly-hypothetical internet connection.

Bring it on! Worst case scenario: I’ll dress them all in something ridiculous and we’ll clown around to camouflage the parts of the session that don’t work.

Crunch time…

Head count: approx 60 - much more than expected

Skillset balance: good to excellent

Internet connection status: quaint

I won’t elaborate too much on the process of how a data expedition works as that is covered by the (now ancient) Guide for Guides.

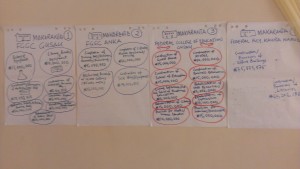

But the principle simple: all teams start with a question e.g.

- “The life expectancy in Botswana all of a sudden dropped sharply at a particular point in time. What was the reason?” or

- “Who really owns these mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo?”

The facilitators then guide them as far as possible along the data pipeline as they can get in the allotted time.

Source: Spending Data Handbook

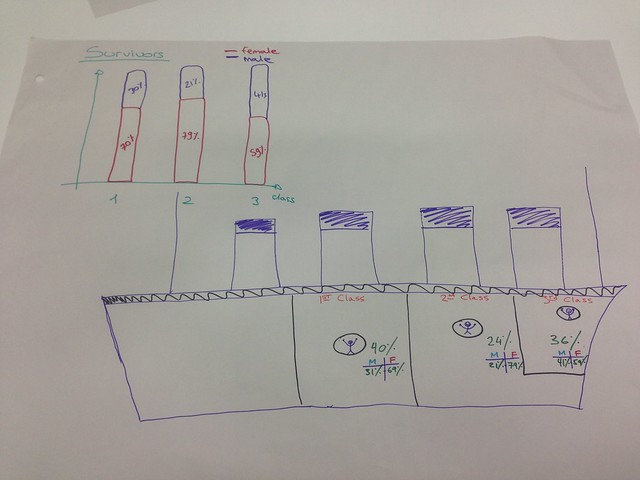

At the end, people present whatever they can. Any output is valid; a clean dataset, a full data visualisation, a paper sketch of what they would have done had they had the time/resources/skills, or even a list of problems they experienced.

Back in the room

I’m astounded by the number of people who have come to the session, the room is packed and … it somehow appears to be working…?!

…People are asking each other if they don’t know how to do something and actually producing results. It’s absolute bedlam and incredibly noisy but it’s working!

Learnings from data expeditions

our inkling was that the only way to really teach data skills was to confront people with a mountain. By forging [their] own path […] data explorers can pinpoint the extra skills they need to develop in order to scale new obstacles, map their own journey and ultimately to tell their own story. The answer may be at the top, but there are multiple routes to the summit – and each will offer a fresh view over the landscape.

Followup blogpost to the first data expeditions

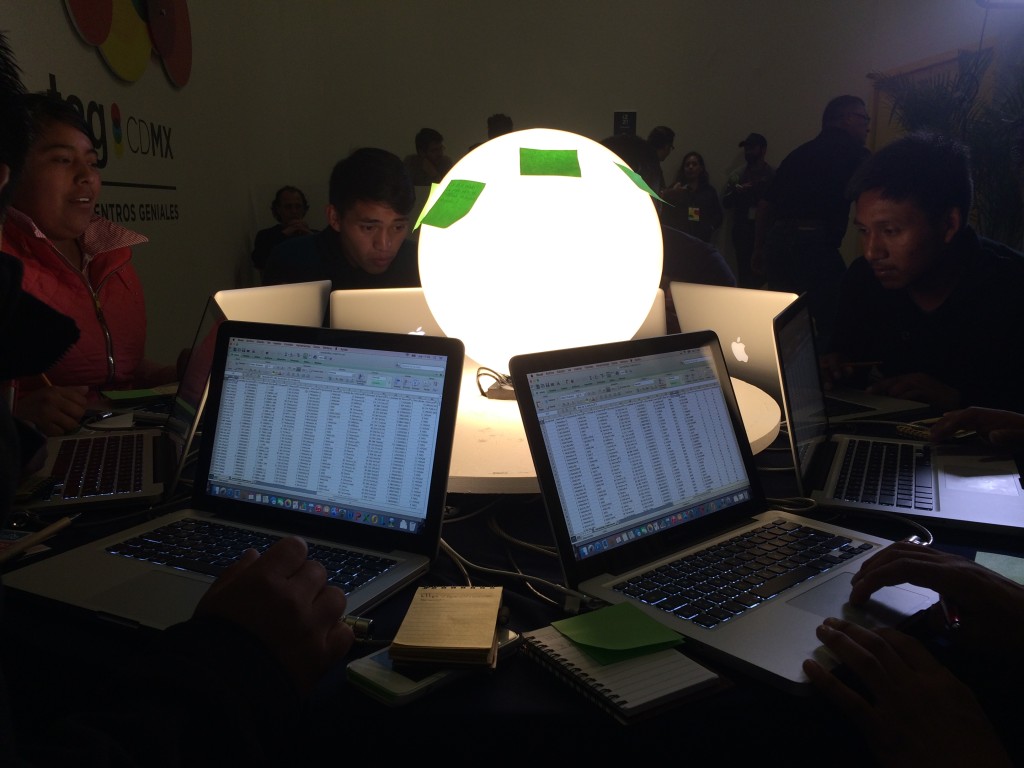

After MozFest, we went on to lead many data expeditions around the world. We had to adapt to many different things: knowledge levels, time constraints, participants who really wanted to get a specific thing from the expedition.

Here is my rundown from the major discoveries of that period:

Number 1: It is very hard to predict what someone will learn from a data expedition – but they will learn something

Everything depends on the course the group takes. It’s hard to know how far the group will even get.

If you are trying to teach a specific skill in a workshop, you either need to stage parts of the expedition very carefully (possible, but lots of work) or, you should probably pick another format.

Number 2: The right people are important, but they’re not the ones you might think.

Most important skillset: topic expertise — you can do a huge amount with basic tools, even if there are no advanced engineers or analysts in the room. All you need is one or two people who have a deep understanding of the topic area. If you are low on data-chops in the room, you’ll need to be more hands-on as a facilitator and probably spend more time helping people to google things. Don’t let it become too much about you showing them things, try and encourage the same self sufficiency as if they were genuinely on their own.

Number 3: Online expeditions can be hairy, but you can make them work.

Online expeditions are particularly facilitator intensive, because people don’t keep the same level of focus as they do in person. Even if they are engaged at the beginning, their attention wanes… they end up in Buzzfeed listicle rabbitholes. For longer expeditions, it’s hard to gauge availability and whether people are stuck. The poor stuck people are left hanging as the only person in their group who can help goes to have a bath or pick up their kid from kindergarten.

The most successful expeditions we ran online were short, a couple of hours to a day max. Both online and offline, a short timeline helps to focus people on their desired outcomes.

Unexpected side effects of data expeditions

Both at MozFest and in the online version, people were forced to spend time with people they wouldn’t normally do. I remember one girl coming up to me and saying, entirely out of the blue:

“I’ve never spoken to a coder before!”

Also online, while a lot of the groups entirely disintegrated, some people used the group structure we had set up to stay in touch or ask for help on data or tech issues long beyond the date that the data expedition was scheduled to finish.

Data expeditions were more than just a teaching tool, they brought people together in a way that working alone on a problem or exercise never could.

The final balance

The success of the Data Expeditions and other in-person formats like Data Clinics or targetted workshops meant that School of Data moved away from being a solely online learning mechanism to one which favoured human interaction.

School of Data did still produce materials, and as community members attest, they are a core part of the identity, but the English resources were usually produced “on demand” when an event was coming up which needed them.

The focus on in-person training also changed the nature of what we produced: more lesson plans and materials suited for in-person training.

As the reputation of School of Data grew, the demand for in-person training did too. This is the reason the fellowship was born and that a lot of what School of Data currently does is skillshare. It is much better for people to learn in their own language, taught by people who understand local contexts than for a small group of Europeans to fly around the world pretending to know everything.

So:

- Get yourself some foundational resources so that you can react quickly to common requests for training.

- Instead of developing material for every topic on the planet, tailor existing resources to specific audiences you are going to work with. If you are working with a budgeting group from Nepal, use budget data from Nepal if you can get it. If you can’t get it, at least use something locally relevant.

- Find yourself some trainers with big ears, who listen more than they talk. A teacher’s job is to understand the problems people are having and provide solutions which are appropriate for them — not to deliver pre-packaged solutions.

Materials are important for sustainability. They can quickly be picked up, translated and shared all across the world. But nothing compares to the reality check that comes from being with the users of those materials in person to make sure you are keeping the project on the right lines.

Postscript

Some of you will have noticed that I promised to write a 5 part series nearly 6 months ago now and have so far produced only 2/5 posts.

The rest of these posts have been sitting on my harddrive, festering and I have been too deliberative to finish them.

On 13th of September 2015, procrastination exterminator and cattle-prod extraordinaire, Michael Bauer, friend and School of Data colleague tragically and unexpectedly passed away.

Michael could not stand procrastination, and never allowed anyone around him to engage in it.

I couldn’t think of a more fitting tribute to you than actually finishing this, Michael. I hope you realised how much things moved forward because of you.

A version of this post appears on Tech to Human as part of the 5 years worth of learnings series.

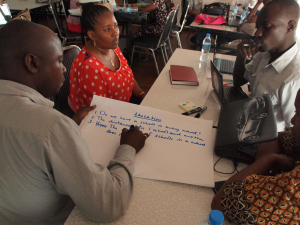

participants share their ideas on how to approach different datasets and how to feed this into an official open data portal that can carry all these datasets together. One of the participants, Aymen Latrach, discussed the problems his team faces when it comes to data transparency about extractives in Tataouine. Other CSO’s like Manel Ben Achour who is a Project Coordinator at I WATCH Organization came already from a technical backgrounds and they were very happy to make use of new tools and techniques while working with their data.

participants share their ideas on how to approach different datasets and how to feed this into an official open data portal that can carry all these datasets together. One of the participants, Aymen Latrach, discussed the problems his team faces when it comes to data transparency about extractives in Tataouine. Other CSO’s like Manel Ben Achour who is a Project Coordinator at I WATCH Organization came already from a technical backgrounds and they were very happy to make use of new tools and techniques while working with their data.

opulation was elderly people in poverty. This was a good example of how to use data to make informed decisions.

opulation was elderly people in poverty. This was a good example of how to use data to make informed decisions.